The US Underreported the Number of International Students by 200,000 Last Year

Bad SEVIS Data is Now Fixed—but the Latest Visa Data Signal Trouble for the Fall

The US government underreported the number of international students by over 200,000 last year. That’s what the revised Student Exchange and Visitor Information System (SEVIS) data (just posted) now indicate.

I discovered this just as I was getting ready to unplug for the July 4th weekend—a friend emailed that the monthly SEVIS data were back up, and what I found stopped me cold. The numbers I'd been using, the numbers we'd all been using, were wrong. Not just a little wrong. 200,000 students wrong.

To be clear: The underlying SEVIS data were accurate, and at no point did the US government “lose track” of any international students. However, beginning in August 2024, the monthly public reports generated from that data and posted on the SEVIS Data Mapping Tool Data website significantly underreported the number of international students.

The story of the “old” (inaccurate) and “new” (corrected) SEVIS data is completely different. I used the “old” data, which (incorrectly) indicated a dramatic drop in international students that started last fall during the Biden administration, while the corrected data show steady growth (+6.5%) from September 2023 to September 2024.

But the latest non-immigrant visa data (F-1, J-1, F-2 & J-2) suggest the last four years of “steady growth” is unlikely to continue.

Looking at the latest SEVIS and visa data together, three things become clear:

how badly the US government botched the count of international students,

what's actually happening with international enrollment as of June, and

why we might see the biggest one-year decline since COVID this coming fall.

The 200,000 Undercount

First, let’s address a huge data fail that led to some unnecessarily bad headlines.

SEVIS is our only real-time window into international enrollment (the 2024/25 Open Doors data won't be available until November).

In early April, I was shocked to discover what appeared to be a 130,000 decline from March 2024 to March 2025. Turns out that was wrong. My analysis was sound—the government's SEVIS data weren't.

In late April, the government removed data from January 2023 to March 2025, citing data quality issues, posting this banner at the top of the Study in the States website where SEVIS data is posted:

I have the “old” datasets downloaded, so I compared them to the “new” datasets just posted. There’s a yawning gap. The errors started in August 2024 and got worse from there.

March to July 2024: The data match, although there’s a negligible discrepancy in May. June and July are identical.

August to September 2024: The gap first appears in August and undercounts the number of international students. The gap widens by September: 1,294,231 (new/corrected) vs 1,091,182 (old/inaccurate) = 203,049 undercount.

October 2024 to March 2025: The old SEVIS data flatline with little variance; the ~200K gap remains virtually frozen.

In mid-April 2025, Cheryl Delk-Le Good of EnglishUSA alerted the Department of Homeland Security (DHS), which runs SEVIS, to the lack of typical month-to-month fluctuations. DHS took the data down by the end of April but provided no official explanation—not when they removed it, not when they reposted it.

Nine months passed between the problem's start in August and the takedown in April. It's still unclear whether anyone at DHS noticed the issues before that mid-April alert.

The SEVIS data quality issues echo another “data fail” under the Biden administration when National Clearinghouse data indicated a 5 percent drop that had to be corrected to indicate a 3 percent increase.

June 2025: Where International Enrollment Really Stands

According to the new (corrected) SEVIS data:

The number of international students has increased by 26% over the past 3 years, reaching an all-time high of 1,294,231 last fall (September 2024).1

SEVIS data now indicate year-over-year growth (6.5%)—more than double the 3% reported in IIE’s Fall 2024 Snapshot, making four years of international student increases since the COVID-19 pandemic.

The total active students grew from 1,025,156 in September 2022 to last fall's peak of 1,294,231 students in September 2024, followed by a slight decline this past spring semester to 1,269,297 in January 2025.

India has firmly established itself as the dominant source of international students–143,000 more than China–with the gap widening. The corrected data contradicts indications of a sudden drop in enrollment from India in the “old” data.

Master's programs have been the primary driver of growth, up nearly 50% with four out of five Indian students enrolled in master's programs.

Bachelor’s enrollment has remained essentially flat with modest growth in doctoral degrees, while relatively small associate-degree enrollment has grown.

Overall growth isn't just driven by India. Emerging source countries like Nepal, Bangladesh, Pakistan, Vietnam, and Brazil are all surging. Meanwhile, China and South Korea have seen declines, along with sharp declines from Saudi Arabia.

I searched for unusual patterns from March through May 2025 that might show the impact of the SEVIS record terminations. I was unable to detect any notable anomalies. The March-to-May decline in 2025 (−1.6%) was smaller than ones in 2023 (−2.3%) and 2024 (−1.9%). So, despite the chaos of those months, the data reveal no signs of which students were affected.

Visa Data Points to Fall Declines

While the corrected SEVIS data is “good news” for this past 2024/25 academic year, the latest non-immigrant visa data is foreboding.

Analysis already indicates that the last three years of student visa issuances show that numbers were already declining even before the pause in June.

From January to May, non-immigrant visas (F-1, J-1, and F-2 & J-2) were already down 8% and F-1 visas were down 14% compared to last May.

India's consulates—Mumbai, New Delhi, Chennai—processed half as many F-1 visas from January to May 2025 as they did last year. China's consulates in Beijing and Guangzhou processed 15% fewer. So did consulates in other traditional sending countries like South Korea and emerging sending countries like Vietnam and Nepal.

The data through May already looked bad for fall enrollment.

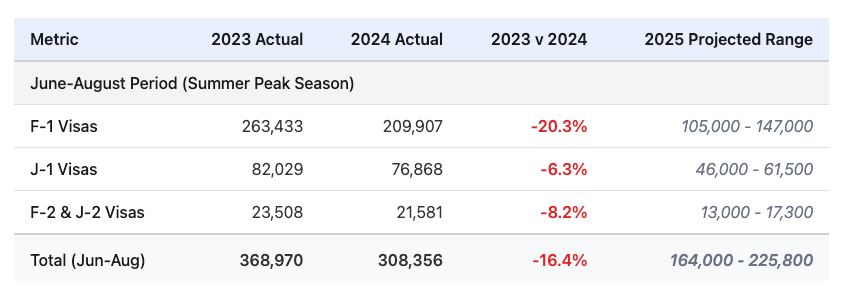

Then came the pause in visa appointment scheduling (May 27–June 26, 2025) during peak processing season.

Now that appointments have resumed, the backlog—plus expanded social media screening for all F, M, and J visa applicants—has slowed everything down.

The math is simple: fewer visa appointments plus slower processing equals fewer students.

We won't know the exact impact until September, but the appointment pause plus expanded screening measures could reduce the number of appointments from June to August by 80,000 to 145,000 compared to the same period last year. This translates into a potential international student enrollment drop of 7–11% this fall—from 1.29 million last year to between 1.15 and 1.20 million this fall.

Moody’s has already warned of the credit risk posed to universities reliant on international enrollment. A decline in international students also poses a risk to US science and innovation, as America’s reputation as a bastion of intellectual freedom and economic opportunity has taken a hit with many international students.

Finally, analysis from the CATO Institute indicates that visa denials reached historic highs last year (41%), under the Biden administration, up from 10-15% a decade ago. Expect similar or higher denial rates under the Trump administration.

Final Thoughts

Shortly after the SEVIS data were taken down in late April, I posted on LinkedIn that I hoped DHS would identify the issues and restore the data promptly.

They did. That's important.

But a 200,000-student gap isn't a rounding error. It deserves an explanation.

DHS fixed the data but hasn't explained how it happened, why it took months to notice, or what has been done to prevent it from happening again.

I hope DHS provides an official explanation. If not, perhaps journalists or policymakers can find out what happened. Errors in SEVIS data occurred under the Biden and Trump administrations. Transparency about what happened isn't about partisan politics; it’s about government data we can trust.

In the coming weeks, I'll analyze what happens if the projected international student enrollment declines materialize, especially as it relates to the future of science and innovation in the US and worldwide.

I'll put current trends in a geopolitical perspective and explore paths forward that reflect this Substack's focus: distributed progress.

Post comments below to share your thoughts and on-the-ground insights for others reading this analysis of the new SEVIS data and non-immigrant visa trends. What are you seeing?

“International students” in SEVIS data include all F-1 (academic) and M-1 (vocational), as well as J-1 (exchange visitors) in designated student categories, maintaining legal status across educational levels—associate, bachelor's, master's, and doctoral programs—whether actively enrolled or participating in Optional Practical Training (OPT), Curricular Practical Training (CPT), or STEM OPT extensions. SEVIS also tracks students in language training, flight schools, vocational schools, and other approved programs, as well as private primary and secondary schools, and public high schools.

Wow, Chris, this is important and very impressive data sleuthing, I really appreciate the clarification. Those trends don’t look good for the coming academic year, but I’m not surprised. I actually think the declines will be much larger when you return to us with more data analysis.