F-1 Visa Issuances (so far) Indicate a Second Year of Decline in New International Student Enrollment in the U.S.

The 14% drop so far this year follows last year's 12% decline, plus unusual "summer melt" patterns last summer — was reduced OPT participation the culprit?

Here’s the TL;DR if you don’t have time to read the full analysis:

Last year, F-1 visa issuance trends showed a significant decline (-12%), with the dramatic fall in Indian F-1 student visas (-34%) being the largest contributing factor to this overall decrease.

The first six months of this year (Sep to Feb) show another significant decline (-14%) compared to the same period last year, with both India and China showing substantial drops (34% and 43% respectively).

Last summer, SEVIS data showed an unusual pattern: a steady decline from May through September and a particularly sharp drop between July and August - a stark contrast to Summer 2023's normal pattern of early dip, August spike.

What was behind this "summer melt"? I explore reduced OPT participation as a potential culprit due to tech industry layoffs, visa processing delays, and uncertain immigration policies.

Now on to the deep dive:

F-1 visa issuance data show concerning signs

I decided to take a look at the Monthly Nonimmigrant Visa Issuance Statistics published by the U.S. Department of State to see what clues it might offer for the current and upcoming academic year.

As the chart below illustrates, F-1 issuance data also points to a downward trend in new international student enrollment for 2024/25.

New F-1 visa trends show a 10% decline last summer

Let’s start with F-1 visa applications based on data from the Monthly Nonimmigrant Visa Issuance Statistics from the US Department of State.

There was a significant overall decline in F-1 visa issuances from 442,391 in 2022-2023 to 389,884 in 2023-2024 (-12%), while J-1 visas held steady (+1%), which would indicate an overall 49,290 year-over-year decline of impacting 2024/25 new international student enrollment, representing the first significant decline since the post-pandemic recovery.

A dramatic decline in Indian F-1 student visas (-34%) was by far the largest contributing factor to the overall decrease in F-1 visa issuances in 2024/25, with mixed results among other countries.

So, what do F-1 issuance trends tell us about the upcoming 2025/26 academic year?

We won’t know definitively until the critical summer months ahead (June, July, and August), but the latest F-1 visa issuance data paint a concerning picture for the upcoming 2025/26 academic year.

We have data up to February 2025, so we can compare the first six months from recent years:

2022-2023 (Sep-Feb): 104,160 visas

2023-2024 (Sep-Feb): 103,261 visas

2024-2025 (Sep-Feb): 88,811 visas

This 14% year-over-year decline persisted across key application months, with December (traditionally crucial for spring enrollment) showing a particularly steep 25% drop, while November fell 8%. Only September and October bucked this downward trend with modest increases.

The decline points toward a potential second consecutive year decline in new student enrollments, indicated by both Open Doors and SEVIS data.

India and China still dominate, but their combined share appears to be declining. There are fewer F-1 visa issuances from a more diverse mix of countries than before, with Vietnam emerging as one example of a growth market.

Here are the takeaways from the two major sending countries:

India's F-1 visas plunged 34% from the same period a year ago—the steepest drop among major sending countries and continuing a multi-year slide.

The Times of India recently reported that “over half of student visa applications from Telangana and Andhra Pradesh are being rejected by US authorities. Even Ivy League admittees are not spared.”

The declines in the US come at a time when the United Kingdom just announced a "landmark" trade deal between India and the UK that could strengthen pathways for international student flows between the two countries.

China's visa numbers also show an alarming decline during the current cycle, with a 43% decline in the September 2024-February 2025 period compared to the previous year's relatively modest 7% reduction, suggesting potential new barriers or changing preferences that are significantly affecting what has historically been one of the most stable international student markets.

Did explosive growth from India suddenly reverse?

India is worth looking at as a case in point because it has singularly been behind much of the recent increases in international student enrollments, and now appears to be the most significant contributor to recent declines. It has also seen a sharp rise in US student visa rejections, which Ragh Singh has outlined in great detail.

Let’s go back and look at enrollment from 2021/22 to 2023/24.

SEVIS and Open Doors data indicate Indian student enrollment grew dramatically, increasing by more than two-thirds in just two years, marking one of the most significant expansions of international student populations from a single country in recent U.S. higher education history.

In this period, Master's programs also experienced dramatic growth, nearly doubling from 215,076 to 319,402 students according to Open Doors. Master’s programs alone accounted for over 80% of the total growth in Indian enrollment.

In her June 2024 article for The Chronicle of Higher Education, Karin Fischer covered the volatility of master’s-level enrollments, noting that while these programs have seen rapid growth-especially among international students-they are historically more sensitive to market shifts.

Fischer’s observation seems prescient:

[The] “seismic rise” in graduate study since the pandemic — and specifically in one- to two-year master’s programs — has led to a spike in eligibility for OPT.

Are we now seeing the other end of that enrollment surge?

Students who completed their master's degrees in May/June would either transition to OPT or depart the U.S. This summer period of 2024/25 is precisely when we would expect the first signs of decline to emerge.

What’s been happening with Optional Practical Training (OPT)?

OPT has been masking broader declines

The number of international students participating in Optional Practical Training (OPT) has shown remarkable growth.

Optional Practical Training (OPT) allows F-1 students to work in their field of study for 12 months after graduation, with STEM graduates eligible for an additional 24-month extension. Crucially, students on OPT maintain their F-1 status and remain counted in SEVIS data despite having completed their academic programs.

OPT now accounts for about 1 in 5 of all F-1 visa holders.

This is particularly notable because OPT has been masking underlying weakness in other degree levels for the last several years.

Between 2014/15 and 2023/24, Optional Practical Training doubled as graduate enrollment surged (40%), while undergraduate enrollment dropped by 15% and non-degree Intensive English programs experienced a steep 60% decline.

OPT has become a critical component of the international education ecosystem. But, over time, the composition of OPT participants has shifted dramatically. Two countries—India and China—now make up the bulk of OPT participants. Together, they account for about two out of every three international students in the program.

The 2023/24 academic year showed a significant acceleration of these trends, with total OPT participation increasing by 22% (from 198,793 to 242,782 participants), including a dramatic 41% increase in Indian OPT participants (from 69,062 to 97,556) and a 12% increase in Chinese participants (from 55,133 to 61,552).

What should we make of the unusual drop last summer?

I've been staring at these numbers for weeks, and things are only getting 'curiouser and curiouser.' It started when I noticed the SEVIS data from March 2024 to March 2025 indicated a shocking 11% drop in international students.

When I first saw these figures, to be honest, my immediate reaction was, "This can't be right.” The number was so eye-popping, it was hard to believe. If true, it would represent the largest non-pandemic decline in international education history—and a stark reversal following historic highs in 2023/24.

But there they were, the data staring me right in the face.

Then, a little over a week ago, the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) removed the SEVIS data from December 2022 to March 2025 from its accessible Data Mapping Tool website, labeling it “under review” but without further explanation. The removed data remains available on the Internet Archive Wayback Machine.

Polly Nash in The PIE reports that SEVIS data showed unusual lack of variability in enrollment figures between August 2024 and March 2025, contradicting normal seasonal patterns observed in previous academic years.

Until DHS completes its review, we should approach specific numbers with appropriate caution.

Could it be OPT “summer melt”?

But, if the summer SEVIS data can be trusted (since it occurred before the unusual invariance in the data that began last fall), we can observe that the May to September timeframe coincides with graduation periods, when master's students would complete their programs and return home or transition to OPT.

Let’s consider the possibility that there was OPT “summer melt”.

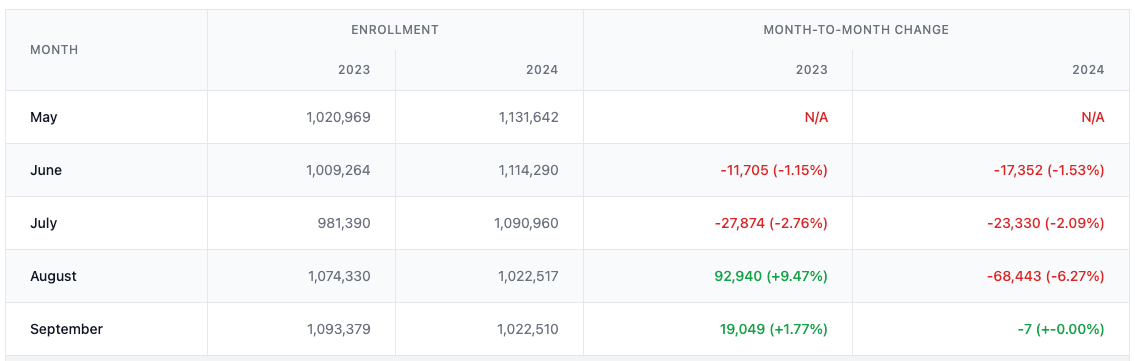

The SEVIS data (under review) suggest potentially different trajectories when comparing the two summers.

Summer 2023 followed normal patterns: an early dip, an August spike, and a 7% overall increase. Summer 2024 broke the pattern, showing steady decline from May through September, with a particularly sharp drop between July and August.

A swing from 7% growth over the summer to almost a 10% decline is a major swing.

DISCLAIMER (Posted 7/7/25)

The Department of Homeland Security's review of SEVIS data found significant inaccuracies in August and September 2024 data releases. The data in the table below were found to be inaccurate in the review.

Read my analysis of the data error and the accurate numbers: The US Undercounted International Students by 200,000 Last Year.Master's programs appear to account for the vast majority of the total decline during this period, particularly among Indian students. Anecdotal evidence, including this comment on my recent LinkedIn post, corroborates these declines:

Is it possible that international students are opting out of OPT?

Beyond just new enrollment declines, the data suggests a complex picture.

About one-third of the decline appears attributable to fewer new F-1 enrollments, which aligns with IIE’s Fall 2024 Snapshot, which noted a “5% decrease for international students studying at their college or university for the first time.”

But what accounts for the remaining two-thirds?

It could be a yet-to-be-explained dramatic anomaly in the SEVIS data itself.

But it's also worth considering another hypothesis:

Reduced OPT participation—whether through students not applying, completing OPT early, or terminating their programs prematurely.

To be clear, the OPT decline hypothesis directly contradicts IIE's Fall 2024 Snapshot reporting "record growth and gains by another 12% in 2024/25" in OPT participation, so with the SEVIS data under review, we should not draw any strong conclusions. The snapshot survey received a 53% response rate, so it is not a census, and there could be a systemic difference between institutions that responded and those that did not.

Several factors warrant consideration of this hypothesis.

Factors that could have driven an OPT “summer melt” last year

Tech industry layoffs and reduced employment opportunities

The tech industry has experienced unprecedented volatility, with massive layoffs from 2023 through early 2025 drastically reducing opportunities in sectors that traditionally employed the largest numbers of international graduates, with increased competition from laid-off workers and lower chances of securing H-1B sponsorship.

Cyclical enrollment patterns after a surge in master’s enrollment

Many people have shared with me that they believe the strong enrollment surge in Master's programs in 2022 may have created a wave of OPT candidates graduating in 2024. Post-pandemic growth in graduate programs initially translated to record OPT participation, before the current decline began as employment prospects deteriorated. Perhaps the students who enrolled in master’s programs in this era opted not to apply for OPT at the rates of previous cohorts or decided to close their SEVIS records before their authorized period ended.

Uncertain employment prospects and unpredictable immigration policies

Employment uncertainty has diminished the perceived value of Optional Practical Training (OPT) as a reliable pathway to long-term employment or residency. Students worry about OPT's future and abrupt policy changes, driving many to seek opportunities outside the U.S. after graduation.

Anxiety is further fueled by new policies that expand federal authority to terminate student status and the specter of stricter enforcement, making long-term planning difficult. The Hindu recently reported, “Over 4,000 international students have received visa revocation notices, and an analysis by the American Immigration Lawyers Association (AILA) reveals that half of them are Indians.”

OPT processing delays and employment timeline challenges

While official processing times have improved to 90 days, graduates report actual waits often exceeding 100 days. A May graduate applying in March might not receive authorization until August. This creates two substantial challenges: few graduates can afford to remain unemployed for such an extended period, and employers are increasingly unwilling to hold positions open without definitive start dates.

I know recent graduates, and this is exactly their predicament. Some international students may decide it’s not worth it, or they simply can’t afford it.

Is this a temporary fluctuation or a more fundamental shift?

To be clear, the September to February visa issuances only indicate what to expect for the Spring 2025 semester. Summer might bring different numbers when most F-1 visas are issued (June, July, and August). The DHS review might also reveal problems with the SEVIS data from last summer.

But the data so far show declines that cannot be ignored. The U.S. higher education system appears to face multiple concurrent challenges:

documented decreases in the new F-1 visa issuances

visa revocation fallout as ICE expands student deportation powers and potential new travel restrictions, and

mixed signals about OPT participation after years of remarkable growth.

These enrollment pressures coincide with broader concerns affecting international student decision-making: rising education costs, growing competition from other destination countries, and perceptions about campus safety.

The coming months will provide critical data.

So, is this a temporary fluctuation or a more fundamental shift?

Historically, international students have made important contributions to America's scientific and economic strength, as well as its cultural vitality, global influence, and the preparation of all American students for leadership in our interconnected world.

During the COVID pandemic, numbers dropped, then rebounded the next year.

Will this year be different?

“One year of decline is a blip. Two years is a trend."

What do you think?

Are you seeing data that might explain part of the reported decline?

Have you noticed changes in OPT participation at your institution?

What else are you seeing that I missed in this analysis?

Share your thoughts in the comments.

Very good stuff.

I noticed the same things. If you check China's f1 numbers 2024/8 to 2025/3, you will find it as fake as a dead body's heart beat.

total bachelor doctor high school master

2022/1

2022/2

2022/3

2022/4

2022/5 257385 96577 53455 0 87215

2022/6

2022/7

2022/8

2022/9 251680 86102 55433 0 93759

2022/10

2022/11 265980 95339 54068 0 97149

2022/12

2023/1 262992 93978 53538 0 96562

2023/2 266109 94662 53559 0 97866

2023/3 257998 91979 52900 0 93267

2023/4 254834 90515 52495 0 91950

2023/5 246094 84542 52282 0 90567

2023/6 238134 79732 52135 0 90071

2023/7 230570 75058 51682 0 86331

2023/8 249275 77583 55748 0 96716

2023/9 254234 79138 56167 0 99139

2023/10 265076 85158 55610 0 103034

2023/11 263962 85597 55119 0 102148

2023/12 261753 85181 54727 0 101217

2024/1 260740 84441 54540 0 101269

2024/2 262156 84577 54496 0 101365

2024/3 255146 82492 54055 0 97151

2024/4 252431 81579 53722 0 95640

2024/5 246761 78927 53476 0 93338

2024/6 237065 73746 53183 2 91852

2024/7 229584 69211 52692 2 88901

2024/8 263530 93950 53329 0 97226

2024/9 263526 93940 53307 0 97251

2024/10 263525 93941 53296 0 97262

2024/11 263523 93935 53283 0 97278

2024/12 263514 93923 53274 0 97294

2025/1 263517 93919 53263 0 97312

2025/2 263514 93920 53230 0 97348

2025/3 263510 93913 53220 0 97363