Five Reasons International Student Numbers in the U.S. are Shifting into Reverse

How these 5 factors are impacting the top 25 sending countries, plus scenarios for 2030

Michael Beckley argues in Foreign Affairs that we are in a new Age of American Unilateralism, where the United States is no longer committed to upholding the liberal international order, but instead morphing into a “rogue superpower”.

Jeffrey Sachs, a staunch critic of the Biden administration’s foreign policy, recently criticized Trump's tariffs, warning: “People should understand we are in one-person rule in the United States. Our political system is in a state of collapse.”

Among the signs of America's new unilateralism:

a 130,000 decline in international students from March 2024 to March 2025 according to SEVIS data, and

a 38% decline in postgraduate international student interest in the US from January-March 2025, according to StudyPortals.

While “record high numbers” make for good headlines, our policymakers need a reality check.

America’s open doors are at risk of creaking shut, inch by inch.

We must understand why this is happening and what, if anything, can be done about it before it's too late. It’s hard to fathom, but the world's premier scientific power is voluntarily dismantling its international talent pipeline.

If nothing changes, 75 years of growth is about to go into reverse.

America’s open doors are at risk of creaking shut, inch by inch.

Five Reasons International Enrollment in the U.S. is Shifting into Reverse

This unilateralist turn manifests in higher education through five major factors.

Visa Denials: Visa denials surged to 41% in 2024, up from 15% a decade ago. Research demonstrates a "chilling effect”– for every 10% increase in the F-1 visa refusal rate, there is a 12% decrease in new international enrollment.

Policy Uncertainty: Talk of new travel restrictions, 1,600+ visa revocations (likely even higher), and promises of “extreme vetting”.

Affordability: Fluctuating currencies and tariff uncertainty make American tuition (and its expensive cities) an increasingly unpredictable financial gamble.

Better Alternatives: Other countries offer high-quality, more affordable education with clearer pathways to work and residency, while the US policymakers consider whether to end or scale back Optional Practical Training (OPT).

Safety Concerns: Headlines about gun violence and xenophobia permeate the social media advice groups that international students rely on to make decisions on whether to study in the US.

For every 10% increase in the F-1 visa refusal rate, there is a 12% decrease in new international enrollment.

How do these five factors impact the Top 25 sending countries?

I decided to look at the impact of these five factors on the top 25 sending countries.

According to the March 2025 SEVIS data, these countries account for 82% (842,813) of total international students (associates, bachelors, master's, doctoral, and language training) in the U.S, so it’s worth taking a closer look.

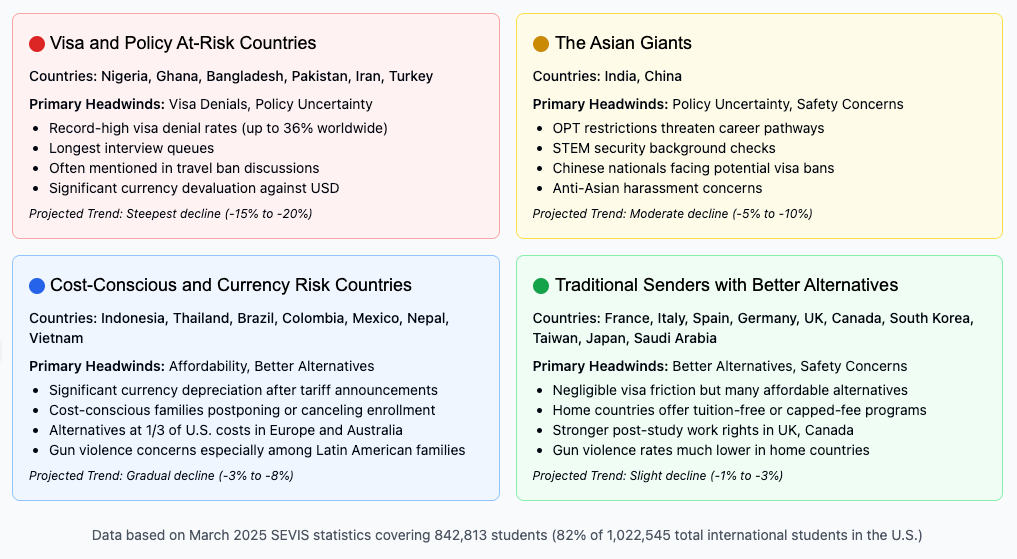

Based on the data, I've clustered the sending countries into four distinct groups that face different combinations of these five factors:

🔴 Visa and Policy At-Risk Countries (Nigeria, Ghana, Bangladesh, Pakistan, Iran, Turkey) face the heaviest burden from visa denials and policy uncertainty.

🟡 The Asian Giants (India, China), where OPT restrictions, pathways to work and residency, and security concerns dominate.

🔵 Cost-Conscious and Currency Risk Countries (Indonesia, Thailand, Brazil, Colombia, Mexico, Nepal, Vietnam), where affordability and currency fluctuations are the primary barriers.

🟢 Traditional Senders with Better Alternatives countries (France, Italy, Spain, Germany, UK, Canada, South Korea, Taiwan, Japan, Saudi Arabia), whose students have quality alternatives, often closer to home.

These clusters aren't meant to be absolute categorizations but rather illustrative frameworks of how combinations of the five factors are impacting different types of international students who want to study in the US. While my analysis focuses on the top 25 sending countries, these same patterns extend beyond these nations.

🔴 Visa and Policy At-Risk Countries

SEVIS data indicate there are 72,398 students from two distinct regions facing narrowing pathways: Africa (Nigeria, Ghana) and Asia (Bangladesh, Pakistan, Iran, Turkey).

Visa friction–with long interview queues and high visa refusal rates–creates the dominant barrier for these countries, while other frictions pile on.

In this must-read analysis from the Cato Institute, David J. Bier highlights that over 250,000 international students accepted to US institutions were denied visas in 2023, with African and South‑Asian nationals bearing the brunt. Denials often come down to “an interview of a lifetime“.

Information about a potential new Trump‑era travel restrictions explicitly lists several Muslim‑majority senders, reviving memories of 2017 and raising fears of sunk‑cost losses if visas are cancelled mid‑study.

Macro headwinds are significant: Nigeria’s naira has been battered, making already‑high U.S. tuition bills more expensive overnight. Meanwhile, alternative destinations look increasingly attractive—Canada’s colleges and Germany’s €0‑tuition master’s recruit aggressively in West Africa and South Asia, offering faster visas and clearer work pathways; families talk openly about “Plan B” when U.S. slots disappear.

Safety signals—from mass‑shooting headlines that dominate WhatsApp groups to anti‑Muslim‑harassment stories circulating among Pakistani and Turkish applicants—cement the perception that, even if one clears the bureaucratic gauntlet, life on U.S. campuses could be risky

Recent analysis from StudyPortals indicates the main countries driving a 38% decline in applications (January-March 2025), include India, Bangladesh, Pakistan, Nigeria, and Iran, with the latter indicating the largest decline (-61.2%), followed by a steep fall from Bangladesh (-54.1%).

🟡 The Asian Giants

China and India account for just over half of all international students in the United States—609,000 of the 1.13 million reported in Open Doors 2024. I have written elsewhere about the risks this kind of market concentration represents.

For India, visa friction is moderate: India’s largest posts processed a record 1.4 million visas in 2023, yet the student‑visa line in Hyderabad still averages 58 days—typical of the 50‑plus‑day waits Indian students now face. Indian applicants are denied visas at much higher rates than their Chinese peers.

For China, student queues in Beijing are only 2 days, and most posts sit under a month, but STEM applicants must often clear additional security screening.

Policy anxiety is high with concerns that the Trump administration could pare back OPT and even revoke active visas, a fear heightened by over 1,500 visa revocations. Stricter work permit regulations and rising student visa rejections are significantly deterring Indian students from choosing the US for higher education. House Republicans have introduced a bill that would bar all Chinese nationals from F‑1 and J‑1 visas on national‑security grounds, underscoring policy risk and uncertainty, even if passage of the bill is unlikely.

Macro headwinds amplify costs. Over the past year, the rupee has depreciated from ₹82 to ₹87 per dollar, driving up tuition fees, accommodation costs, and daily expenses.

Outbound data show double‑digit gains of Indian enrollments in Russia (+59%), Germany (+68%) France (+33%), New Zealand (+354%), and Ireland (+49%) with declines in Canada (-41%), the UK (-28%), the US (-13%), and Australia (-12%). Mirroring US trends, the British Council projected "peak India” for the UK, citing tightening visa restrictions depressing demand.

Safety signals remain a potent narrative layer. Gun‑violence incidents such as the Florida State University shooting dominate Chinese and Indian social feeds, reinforcing parental risk perceptions. Simultaneously, rising reports of anti‑Asian harassment on U.S. campuses add to safety concerns and the sense that the country is less welcoming.

Visa congestion is tolerable for now, but any new OPT shift or visa restrictions would likely trigger another double‑digit drop—on top of the 28% decline (Mar 2024-Mar 2025) already recorded for India—redirecting hundreds of thousands of students toward other lower‑risk destinations.

🔵 Cost-Conscious and Currency Risk Countries

SEVIS data reveal 162,923 students from cost-sensitive growth markets spanning Southeast Asia (Indonesia, Thailand, Vietnam), South Asia (Nepal), and Latin America (Brazil, Colombia, Mexico)

Money shocks from a stronger U.S. dollar dominate the concerns of these students. Tariff headlines knocked emerging‑market currencies—Mexico’s peso, Indonesia’s rupiah, and Brazil’s real down significantly in a matter of weeks, instantly inflating dollar‑denominated tuition bills. Families fear further currency fluctuations, many postpone or cancel bachelor‑level and language‑training enrollments, the two segments most exposed to out‑of‑pocket costs.

So, even though student‑visa queues are relatively short, students are pivoting to more affordable destinations. Portuguese and Spanish universities pitch master’s degrees to Brazilians at roughly one‑third of the U.S. sticker price, Australian institutions tout four‑year post‑study work rights to Indonesians, Thais, and Vietnamese IT majors, and Canadian colleges still advertise a straight PGWP‑to‑PR ladder even as Ottawa rolls out 2025 intake caps.

Finally, safety worries—especially U.S. gun‑violence headlines, which surveys place among the top concerns for Latin‑American parents—tip the balance when costs are already stretched.

🟢 Traditional Senders with Better Alternatives

SEVIS data record 173,318 students from countries with attractive alternatives across Europe (France, Italy, Spain, Germany, United Kingdom), Asia (South Korea, Taiwan, Japan), North America (Canada), and the Middle East (Saudi Arabia)

Students from these countries face negligible visa friction, but they have plentiful — often more affordable — domestic and regional alternative destinations to pick from with clear work rights.

France caps public‑university master’s tuition at roughly €3,879 per year, Germany offers zero‑tuition English‑taught master’s programs, Canada still links study to a Post‑Graduation Work Permit of up to three years, and the UK’s Graduate Route guarantees at least two years of post‑study stay time. These alternatives heighten substitution pressure every time U.S. costs rise.

Policy anxiety is comparably low for this cohort: none of the countries mentioned appear on the draft lists of expanded Trump‑era travel restrictions, and their own outbound work‑rights regimes are stable.

Macro headwinds add real cost. The currencies of these countries weakened against the dollar after the Trump’s announcement of tariffs, pushing up the price of U.S. tuition and living costs and prompting families to re‑run their ROI math.

Like all international students, safety (particularly gun violence) is a top concern for both students and their families. There are much lower rates of gun violence in their home countries, with increasing disappointment in America’s inability to control it.

Scenarios for 2030

We have explored five reasons international student enrollment is going in reverse:

record-high visa denial rates,

policy uncertainty under Trump's administration,

currency fluctuations making U.S. higher education unaffordable,

stronger pull factors from alternative destinations, and

growing safety concerns.

Now let’s consider three scenarios for U.S. international enrollment by 2030:

Scenario 1: Course Correction

This scenario marks a course correction from current policies. The U.S. expands visa processing capacity, preserves OPT's three-year duration for STEM graduates, and implements comprehensive H-1B visa modernization. A moderating dollar and minimal tuition increases do not exacerbate affordability challenges. China and India return to steady growth, while U.S. institutions diversify enrollment across a broader range of countries and visa denials subside worldwide. The result: 20–25% growth to 1.3–1.4 million students, a return to steady growth per year.

Scenario 2: Structural Stagnation

This scenario depicts a prolonged period of international enrollment stagflation—a stagnation of growth combined with persistent friction in cost, access, and policy. Visa processing stabilizes, but denial rates remain at historic highs. OPT survives but with intensified compliance monitoring, leaving students and employers uncertain about eligibility, timelines, and long-term work prospects. Chinese enrollment continues its gradual decline, while bilateral cooperation creates a boom-bust pattern of enrollment from India and other countries. Cost-sensitive students seek predictability elsewhere. By 2030, U.S. international enrollment looks remarkably similar to today—sideways movement—making this the first full decade in 75 years without sustained growth.

Scenario 3: Unilateralist Shift

This scenario reflects America becoming a “rogue superpower”, what Beckley describes as “neither internationalist nor isolationist but aggressive, powerful, and increasingly out for itself.” OPT is curtailed to one year for all graduates, knowledge security concerns prompt expanded travel restrictions targeting key sending countries, and visa denials either remain at historic highs or increase further. U.S. international enrollment could decline as much as 10-25% in the next five years.

The Questions Before Us

The US already enrolls 130,000 fewer international students than a year ago– before the NSF and NIH cuts, visa revocations, and any potential new travel restrictions have gone into effect.

America’s strength—its flexible institutions, openness to talent, and the ability to attract bright, creative people–has shifted from a pillar of America’s economic, scientific, and soft power to populist and security-driven calls to curtail international student flows.

If you don’t believe me, take a look at the comments in response to my post on X celebrating the 130,000 drop in international students, mostly due to a significant decline (-28%) of students from India.

Here’s just one example of the reaction on X:

But that sentiment is not limited to social media platforms like X.

Last week’s Boston Globe featured an editorial, “Why US colleges should cut back on international students,” signaling that the desire to reduce the number of international students at US universities is becoming more mainstream.

Smarter Policy – Not Better Marketing

I don't believe this is just another cyclical fluctuation, but more likely a fundamental restructuring. These trends do not appear to be "temporary shocks" like ones in the past (COVID, global recession, sequestration, etc.). Rather, they signal a potentially long-term reversal in international student enrollment patterns in the U.S. that won't be easily resolved by economic cycles or more diversified recruitment strategies.

The five factors represent systemic challenges, not marketing problems. They require smarter policy and a national strategy for international education.

affordability issues stem from macroeconomic currency dynamics;

better alternatives reflect long-term shifts in student mobility;

safety concerns require societal-level interventions; and

visa denials and policy uncertainty are likely to persist in the near term.

For American higher education to maintain its historic position, these structural impediments require coordinated federal policy solutions—a recognition that America’s higher education leadership requires a national strategy that reflects a historic strength–a country that welcomes bright minds from across the world.

National Identity – Not Numbers

The 38% plunge in international student interest in the US isn't merely a statistic—it's a leading indicator of the new American unilateralism.

To be clear, America isn't alone in its inward turn:

High-income Western nations are systematically dismantling decades of internationalization policies in what Hans de Wit calls a "radical undoing". Australia, Canada, the Netherlands, and the United Kingdom are all implementing caps to reduce international student numbers, while strengthening "knowledge security" measures.

Meanwhile, China is expanding its educational influence through the Belt and Road Initiative, transforming Chinese universities into "magnet institutions" for developing countries in a "post-American world". Post-PhD students are at record levels. And, while DOGE dismantled the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID), China is strategically expanding educational partnerships across Asia, Africa, and Latin America through initiatives.

But it’s not too late.

Beckley argues in his analysis, “If recognized and redirected, these forces could form the foundation of a more focused and sustainable strategy.”

Change is possible if policymakers lead efforts to:

Lower visa denial rates for minor infractions and streamline application processes.

Provide clear, stable pathways to work (e.g., maintain OPT for STEM graduates, create Cap-Exempt H-1B Pathways and Specialty Occupation Visas).

Reduce policy volatility and signal a long-term commitment to international talent.

Large majorities of Americans see the benefit of America’s openness to international talent.

The question before America is not about numbers but about its national identity.

On Sunday, Boston commemorated the 250th anniversary of Paul Revere's midnight ride—a call to resist the rule of an unelected monarch.

America’s turn towards unilateralism marks another defining moment:

Is a country that has opened its doors for 75 years beginning to reverse course, slowly creaking them shut, under one-person rule?

What do you think?

What do you think of the 5 factors? Anything I’m missing?

What am I overvaluing or undervaluing in the 2030 scenario analysis?

Why do you think there’s been a 38% drop in interest this year?

I’m pretty sure there’s much more to share than what I was able to write up in this short analysis, so share your thoughts with other members of the Distributed Progress community in the comments below.

You mentioned OPT, but didn't explain what the acronym stands for (Optional Practical Training - I had to look it up), or what it does. Plain english, please.

Why numbers are dropping:

If a recession is coming, and American unemployment rises, it will be difficult, especially at public universities, to justify admitting & accommodating international students to taxpayers. Yes, these students are paying full freight, but they're more costly than most American students. As in: A university has to have a visa management office/staff/computer system. Not free, not cheap. There's more, but you get the idea.