Up Next: OPT

Fortunately, the OPT Observatory Arrived Just In Time for an Evidence-Based Debate

OPT reform is coming. Major restructuring at minimum, outright elimination possible. When the “breaking news” alert arrives on your phone, don’t be surprised.

It will happen all of the sudden, just like the 6,000+ SEVIS record revocations, the 3-week “visa pause,” the proposed elimination of Duration of Status (DOS), and the announcement of a $100K fee for H-1B visas.

The timing is unclear. But some kind of action appears likely. And, I expect sometime within the next few months.

The signs are there:

On the executive front, USCIS Director Joseph Edlow publicly pledged in July 2025 to “terminate” OPT and eliminate STEM OPT extensions—a commitment that positions DHS to act unilaterally through regulatory authority, bypassing Congress entirely.

On the legislative front, Senator Jim Banks (R-IN) introduced S. 2821 in August to abolish the program through Senate legislation, while Representative Paul Gosar (R-AZ) reintroduced parallel legislation (H.R. 2315) in the House that same spring. Senator Tom Cotton introduced the OPT Fair Tax Act (S. 2940) in September, to subject F-1 students’ OPT employment to FICA taxes.

Adding pressure on the executive branch, Senator Chuck Grassley (R-IA), chairman of the Senate Judiciary Committee, sent a September 2025 letter to DHS Secretary Kristi Noem demanding the agency immediately stop issuing work authorizations to student visa holders. Grassley’s rationale reframes the debate: OPT isn’t a labor market problem—it’s a national security threat that “puts our nation at risk of technological and corporate espionage.”

The Department of Homeland Security (DHS) is the most likely channel for any major change to the Optional Practical Training (OPT) program.

Federal courts have affirmed DHS’s regulatory authority to issue, modify, or rescind OPT through notice‑and‑comment rulemaking.

DHS’s current Unified Regulatory Agenda includes a new rule, Practical Training (RIN 1653‑AA97) that would “amend existing regulations to address fraud and national security concerns, protect U.S. workers, and better align the program’s goals with its educational purpose.”

The measure remains at the proposed‑rule stage and has not yet been published in the Federal Register. When released, the comment periods would run 30-60 days, and the full process typically takes 6-12 months. So, a proposal in the next few months would mean implementation before the end of 2026.

Yet the announcement itself, before official implementation, would matter.

A move to eliminate or significantly restrict OPT would thrust 240,000+ international students currently on OPT into immediate uncertainty and strain the 2026-27 enrollment cycle as prospective students recalculate whether American degrees remain worth the investment without post-graduation work authorization.

Be ready — or not, at your own risk.

How the OPT Observatory changes the debate

Fortunately, the Institute for Progress released the OPT Observatory at the perfect time: before the breaking news alert.

Violet Buxton-Walsh spent the past year creating the OPT Observatory, “the most in-depth public resource on how the US retains international students after they graduate.”

The OPT Observatory data won’t settle the debate, but they will sharpen it. And sharp debates, grounded in evidence, are how democracies make choices about their futures on purpose.

The dataset is the first institution-level, cohort-based map of OPT usage—showing who participates, where they work, and which states retain them. Abstract arguments about whether OPT matters now yield to concrete evidence about how much.

Until now, analyzing OPT meant choosing between extremes: aggregated data (SEVIS by the Numbers) or institution-level enrollment without employment outcomes (Open Doors).

The OPT Observatory fills the gap by making F-1 microdata publicly explorable for the first time.

It tracks graduation cohorts, showing what share of each graduating class uses OPT, which employers hire them, and where they work.

Three groups can finally answer questions they couldn’t before:

Universities can benchmark OPT rates against peers

States can quantify in-state versus out-of-state talent flows

Policymakers can see which programs convert education into workforce participation

The OPT Observatory lets us look at what actually happened from 2010-2022 with give granular detail.

What is OPT? How much has it grown?

First, some history.

(Feel free to skip to the next section if you’re familiar with OPT.)

OPT began as modest permission for international students to gain practical experience after graduation—12 months for most fields, extended to 36 months for STEM graduates in 2008.

Definition. Optional Practical Training (OPT) is work authorization for F‑1 students to gain post‑degree experience in their field—12 months for most, up to 36 months for STEM graduates. It has quietly become the single largest on‑ramp for U.S.-trained international talent to enter the American workforce.

But modest permissions have become load-bearing structures.

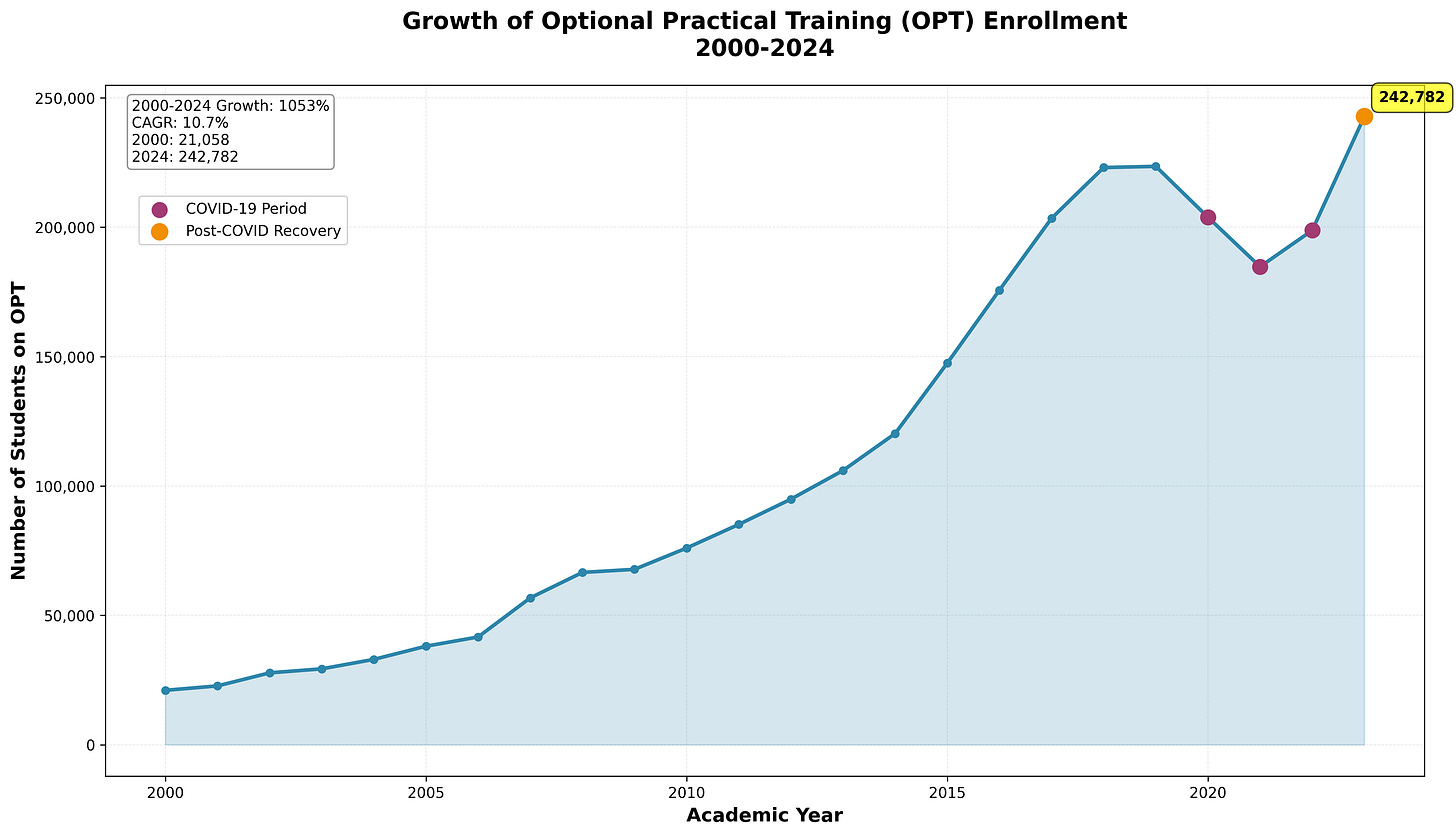

The 10X growth of OPT over the last 25 years can be traced through IIE Open Doors data marked by key shifts in OPT policy:

2000-01: Baseline year, pre-STEM expansion: 21,058

2008-09: First major STEM OPT expansion (extended to 29 months for STEM graduates): 66,601

2016-17: Second STEM OPT expansion (duration extended to 36 months): 175,695

2023-24: Recent all-time high; OPT drives most international student gains: 242,782

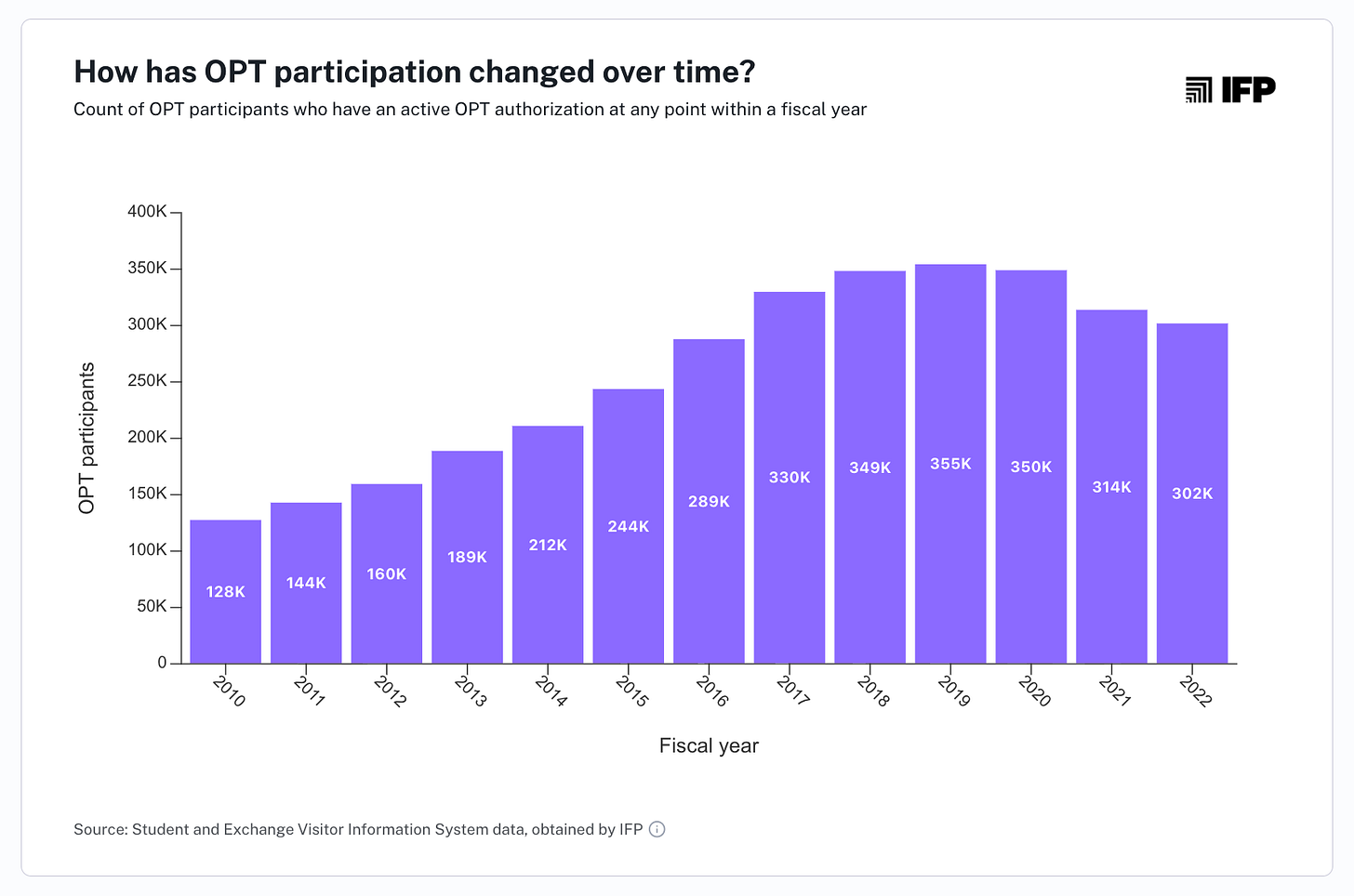

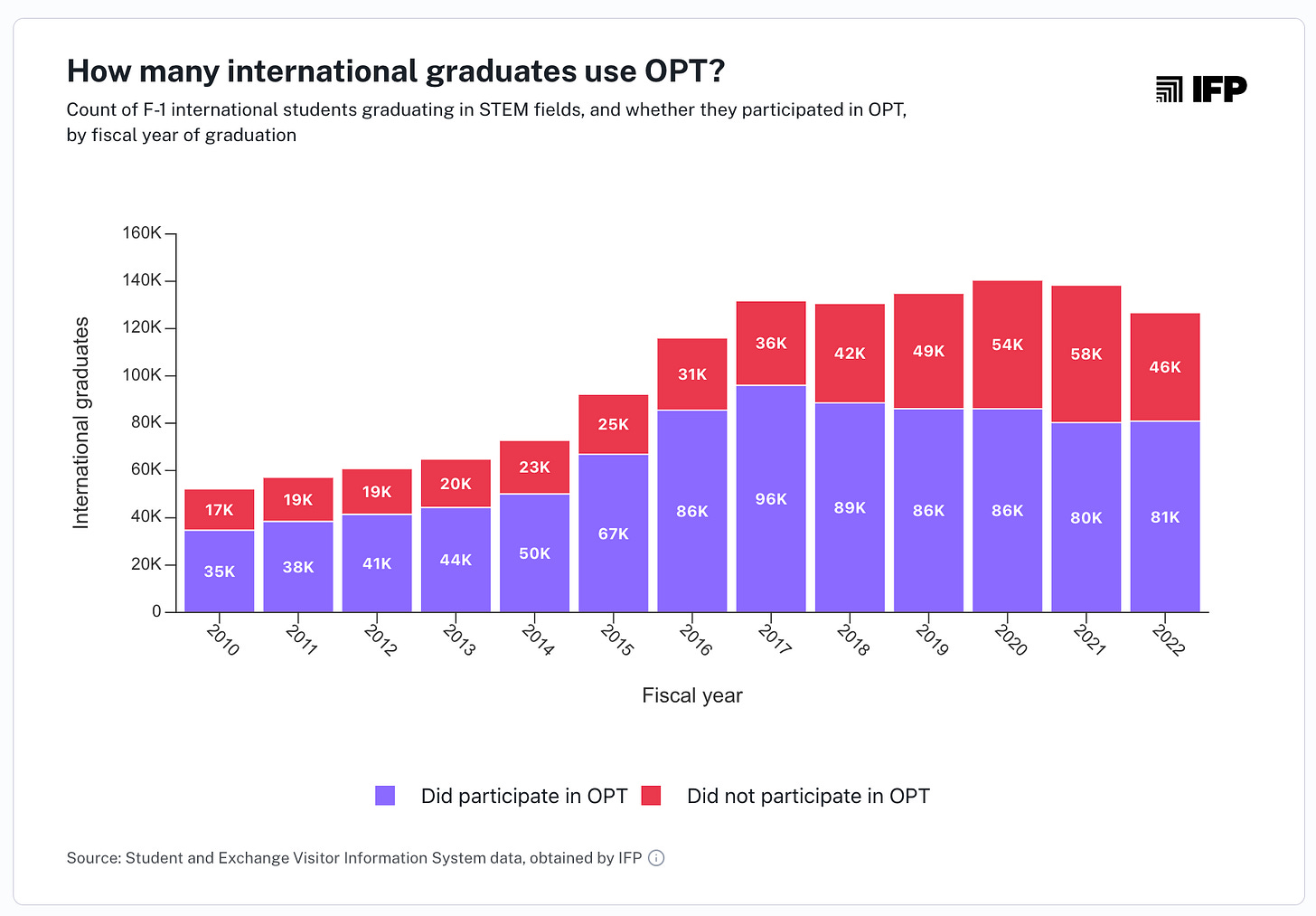

The OPT Observatory data traces the growth of OPT from 2010 to 2022:

Note: The SEVIS numbers used in the IFP analysis are generally higher then Open Doors OPT data because they represent the immigration system count of active F-1 OPT holders, while Open Doors reflects self-reported, institutionally affiliated OPT participants. While IIE data shows year-over-year growth and all-time high in 2023-24, SEVIS data indicates a peak in 2019.What are some highlights of the OPT Observatory data?

We now have definitive answers to some key questions:

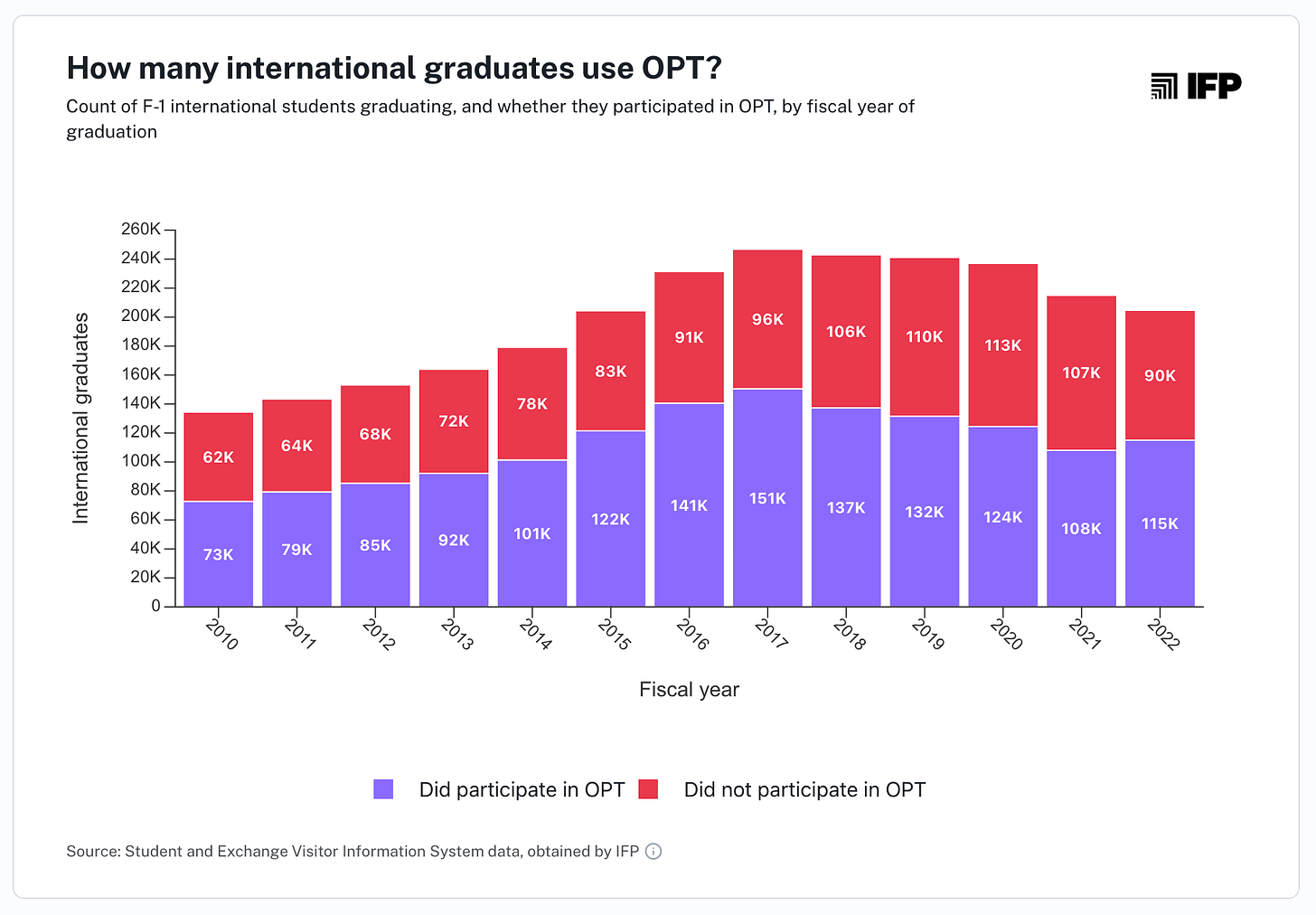

Q1. How common is OPT take‑up after graduation?

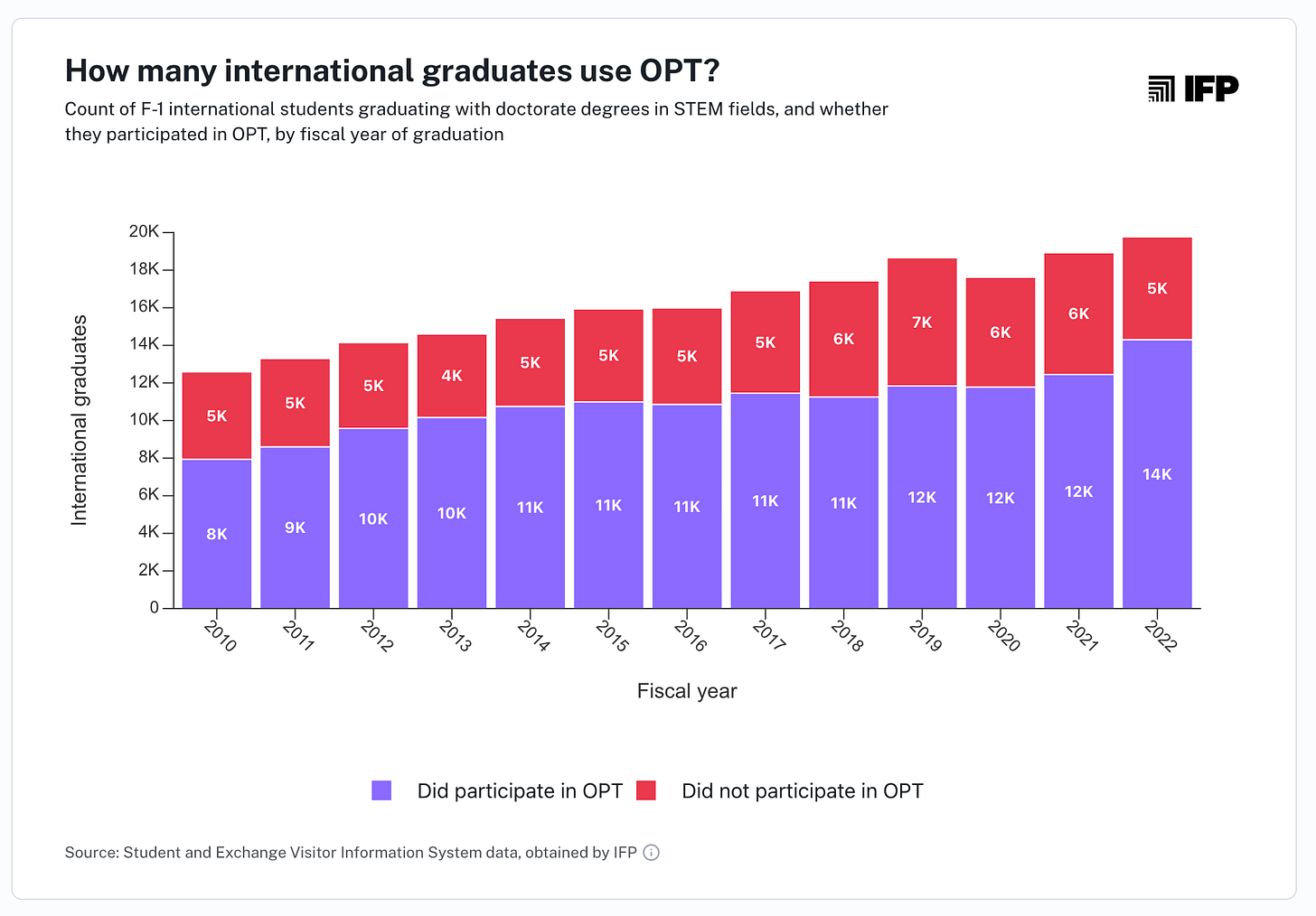

Across 2010–2022, 56% of all international graduates used OPT—and the share is higher for master’s and doctoral students. In 2022 specifically, 64% of STEM graduates vs. 44% of non‑STEM graduates participated; 67% of PhDs and 59% of master’s graduates used OPT.

Q2. Which graduates are most likely to use OPT?

STEM PhDs are the highest‑participation group: 74% of STEM doctorates used OPT over the period, formalizing what universities long suspected but could not show cleanly in public data.

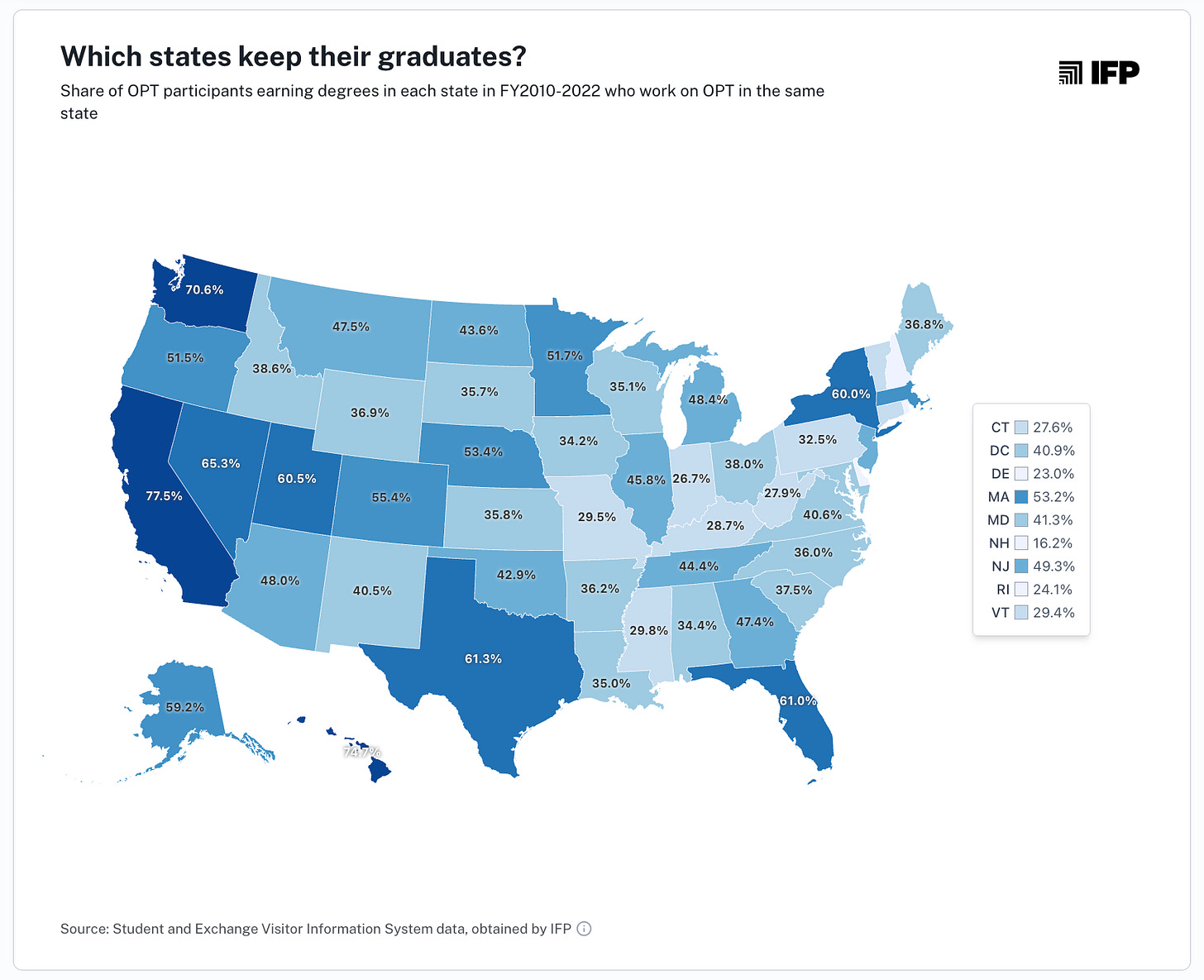

Q3. Which states actually retain their international graduates on OPT?

States with thick labor markets—California, Washington, Texas, Florida, Utah, Nevada, even Hawaii—keep over 60% in‑state.

By contrast, small New England states like New Hampshire (16%) and Delaware (23%) lose most graduates to neighboring states.

Q4. How much variation exists across institutions? Who “punches above their weight”?

With 3,300+ institutions and degree/field filters, universities can finally benchmark campuses on an apples‑to‑apples basis: share of graduates who use OPT by cohort, field, and level. They can see exactly where they under‑ or over‑perform peer sets and identify employer ecosystems to strengthen.

How would elimination (or reform) of OPT impact international enrollment?

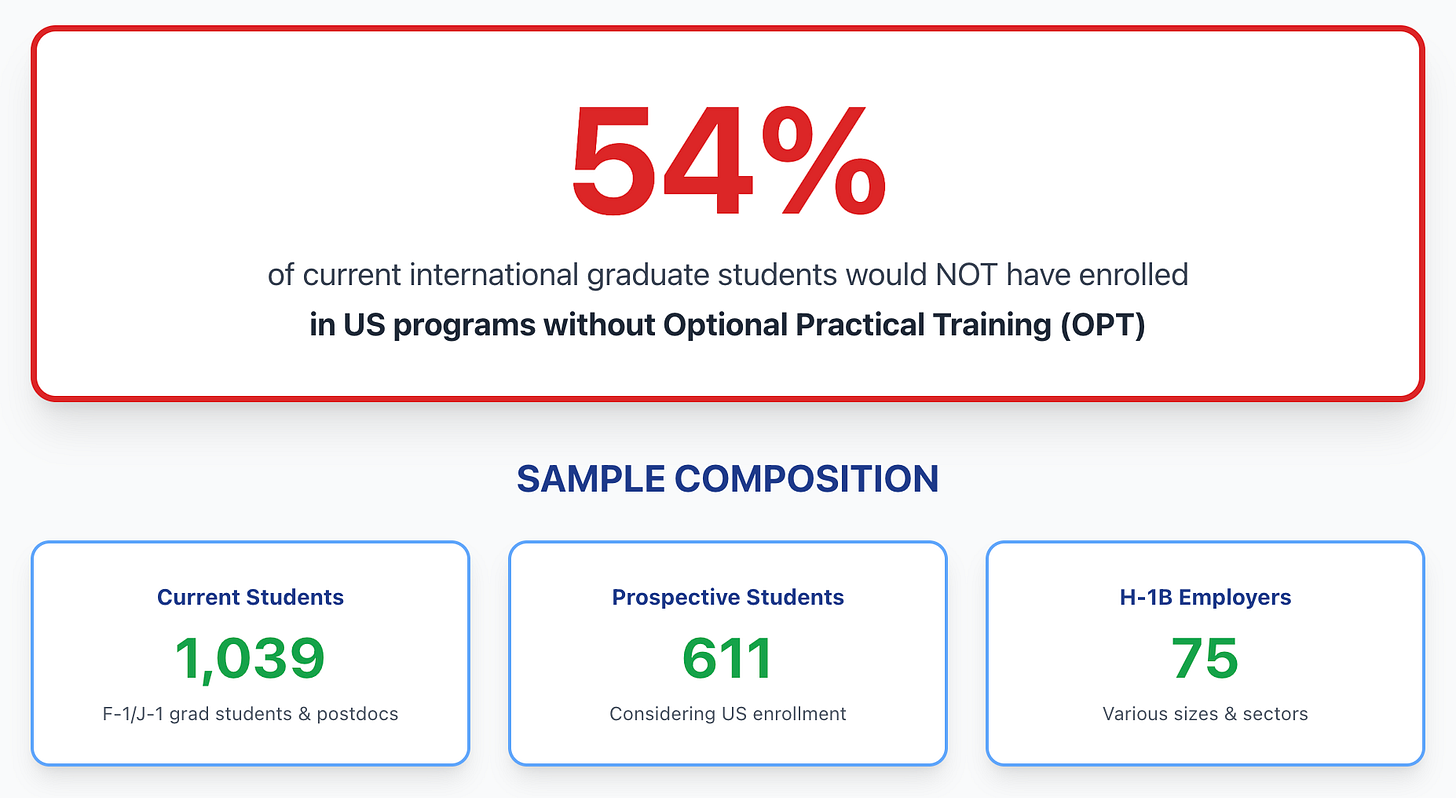

The recent Institute for Progress and NAFSA survey make the risk concrete: 54% of current international graduate students say they wouldn’t have enrolled without OPT. Not “maybe would have reconsidered”—wouldn’t have enrolled.

This is what policy economists would call a revealed preference cascade:

Students choose the U.S. because of post-study work rights

Universities structure recruitment around students who want OPT option

Employers build hiring pipelines assuming OPT access

Research labs depend on talent willing to commit years to projects

The 2025 OECD Education at a Glance reports highlights how international students are making choices based on housing, affordability, and labor market opportunities.

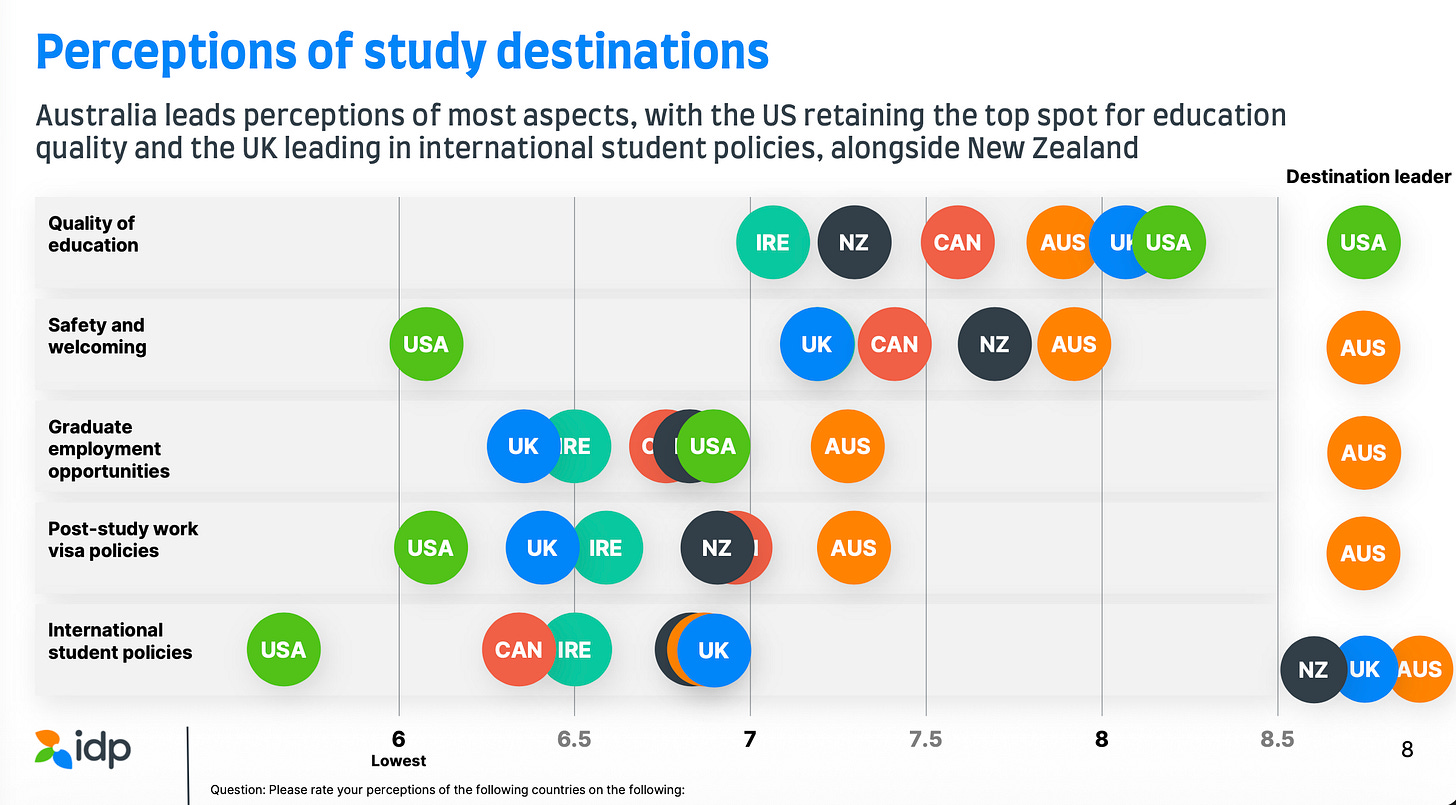

The most recent IDP Emerging Futures 8 report sheds lights on the impact of OPT elimination. While the U.S. ranks first in terms of “quality of education”, it already ranks last in “post-study work visa policies” and “international student policies”.

IDP chief partnerships officer Simon Emmett told Polly Nash of PIE News, “When the rules change, without warning or clarity, trust falls away. Students hesitate, delay, or choose to study elsewhere.”

What would be the impact if OPT was eliminated?

If executive action eliminates OPT in late 2025 or early 2026, the enrollment shock would impact the 2026-27 enrollment cycle and reverberate over the next few years.

STEM graduate programs could potentially face sharp drop within two years, since these students have the strongest post-study work expectations according to the OPT Observatory data.

Three data points anchor this expectation:

A IFP/NAFSA survey found that 54% of current students wouldn’t have enrolled without OPT—the strongest deterrent tested—while prospective enrollment would drop 29% if OPT were eliminated. While survey responses typically overstate behavioral change, the magnitude and consistency suggests genuine policy sensitivity.

Visa uncertainty alone produced enrollment declines during the first Trump administration (2016-2020) without eliminating any programs

As a counterfactual example, Germany’s international enrollment surged 38% (2015-2022) after expanding post-study work rights to 18 months

Speed of implementation will amplify or dampen the shock.

Phased elimination with grandfathering would dampen shock; immediate termination would amplify it.

Institutional impacts would likely be uneven.

Regional public universities would face a perfect storm: declining state appropriations, shrinking domestic enrollment, and disappearing international students. Many will close departments or cut graduate programs; some may not survive.

Elite research universities like MIT, Stanford, and Princeton would likely weather these pressures better due to strong global reputations and flexible recruitment strategies provide cushion, but they too would feel the impact.

Would domestic PhD enrollments rise enough to offset international losses?

Probably not quickly. Domestic students face opportunity costs—foregone wages averaging $60,000+ annually, mounting debt, five-to-seven-year time commitments—that international students with OPT pathways can justify through post-graduation earnings. Labor markets don’t adjust instantly.

What is the path for evidence-based reform?

Universities can’t predict the timing of the administration’s OPT policy move, but they can prepare for potential scenarios. The OPT Observatory is built for this exact moment.

Map exposure and quantify economic impact

The OPT Observatory lets universities trace actual pathways from matriculation through graduation to workforce participation. That evidence matters for trustees, state-level policymakers, and employers who depend on the talent pipeline.

Universities should look at:

How does your institution’s OPT take-up rates compare regionally and nationally?

Which programs would lose the most international graduate enrollment without post-study work authorization?

Do international graduates stay in-state, fueling regional economies, or migrate elsewhere?

Which companies rely on your institution’s talent pipeline?

Build the case for evidence-based innovation policy

The restrictionist critique has a point:

OPT operates through regulatory discretion rather than Congressional authorization. The program has grown from 21K participants in 2000-01 to over 242K today without explicit legislative approval. Some employers game the system—paying below-market wages, using trainees as substitutes for permanent hires.

But elimination of OPT runs counter to strong economic evidence.

When top economists who study innovation policy rated all available options for raising U.S. innovation, they chose high-skilled immigration as both most effective and most proven.

When the University of Chicago asked 80 leading economists whether more highly educated foreign workers would benefit the average American citizen, 89% agreed. When asked if sharply reducing high-skilled immigration would raise domestic employment, 0% agreed.

The OPT Observatory makes better policy design possible.

Foreign graduates of U.S. universities drive measurable gains in innovation, economic productivity, and job creation for Americans at all skill levels.

The question isn’t “immigration good or bad”—it’s how to design science and innovation policy channels talent toward national priorities, or continue with an ad hoc system that redirects international student flows to competitor nations.

Today’s OPT forecast? Reform with a chance of elimination

Outright elimination of OPT would be a bold and risky move. Yet the Trump administration has already moved decisively on SEVIS revocations, Duration of Status, and H-1B reform. Policy tracks political momentum.

Expect major restructuring. And potential elimination.

The status quo survives only if immigration fades from the political agenda, so it is unlikely that OPT will be spared before the mid-terms.

For immigration restrictionists, reversing OPT’s 10X growth over 25 years would deliver a signature victory, something establishment policymakers would view as a blow to American scientific and economic leadership.

Universities will need to approach OPT reform similar how they coordinated theor response to the 15% indirect cost cap. Within months, they convened stakeholders, developed the FAIR model for indirect costs, and created space for compromise.

OPT reform demands the same discipline: convene stakeholders, speak with one voice, propose alternatives addressing legitimate concerns, and act while windows remain open.

The political window is narrowing.

Expect that OPT alert on your phone.

Perhaps by the end of the year.

Maybe I’m wrong. But recent moves signal it’s increasingly likely.

So, when the alert arrives, don’t be surprised.

A few programming announcements:

MIT Debate: Are U.S. Colleges Too Dependent on International Students?

On Thursday, November 6, 2025, the MIT Free Speech Alliance, joined by the MIT Open Discourse Society, will host its fall campus debate, where I’ll be debating the following proposition:

RESOLVED: American Universities are too dependent on international students.

David Freed and I will be debating against the motion. James Fishback and Nathan Halberstadt will be debating for the motion.

Anant Agarwal, professor post-tenure of computer science at MIT, founder of edX, and chief academic officer of 2U, will moderate the debate.

The debate is free and open to the public. If you’re in the Greater Boston area, I’d love for you to come out so we can connect. Learn more »

Any Questions for Sonali Majumdar?

I’ll be interviewing Sonali Majumdar, author of the new book Thriving as an International Scientist: Professional Development for Global STEM Citizens.

Email me chris.glass@bc.edu any questions you’d like me to ask her. I’d love your questions to be part of the conversation.

I’ll post my interview with her on this Substack in mid-November.