What OECD's Demographic Decline Signals for International Student Mobility

OECD’s Education at a Glance 2025 shows how demographic decline and post-growth pressures are shifting international students from “filling seats” to “filling gaps”–reshaping who moves, where, and why

📢 I’ll be at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) on November 6 at 7:00 pm ET in the Wong Auditorium debating the motion: “US universities are too dependent on international students.” Learn more at the end of this post.

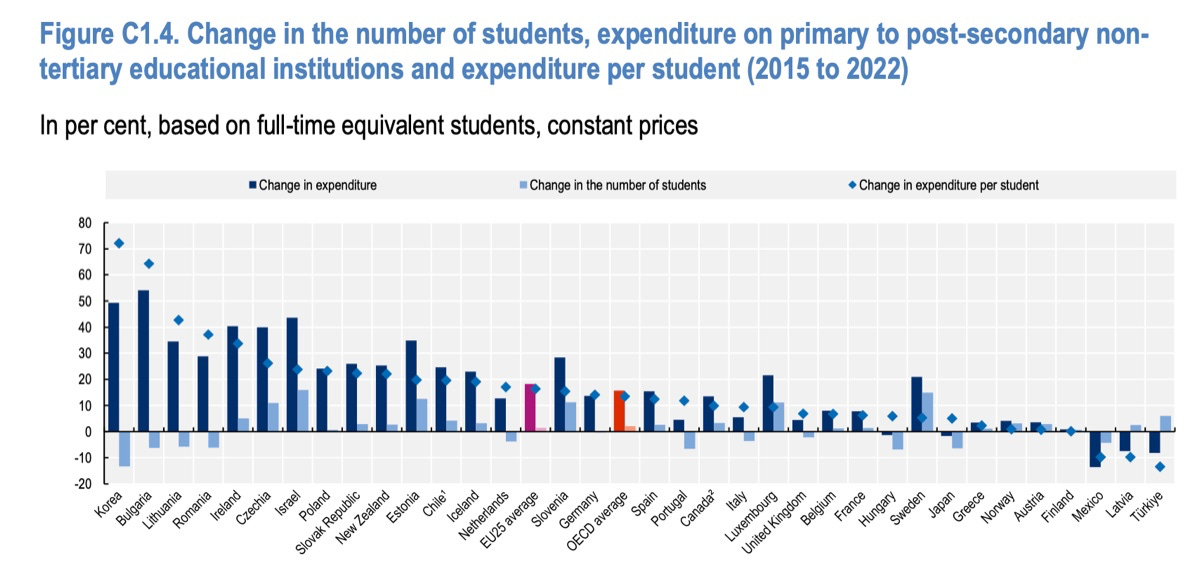

The just-released OECD’s Education at a Glance 2025 report shows that international students are not just “filling seats” but “filling gaps” left by shrinking cohorts in advanced economies, where demographic decline now collides with structural post-growth pressures.

From expansion to demographic stagnation (or decline)

Universities built their business models on a simple assumption: more students would always be coming.

That assumption is breaking faster than anyone expected.

The Economist recently revealed that global fertility rates are plunging far ahead of official projections.

Turkey's birth rate collapsed to 1.48—a level the UN didn't expect until 2100. Similar shocks are hitting everywhere from Colombia to Thailand. The world's population may peak in the 2050s and start shrinking for the first time since the Black Death.

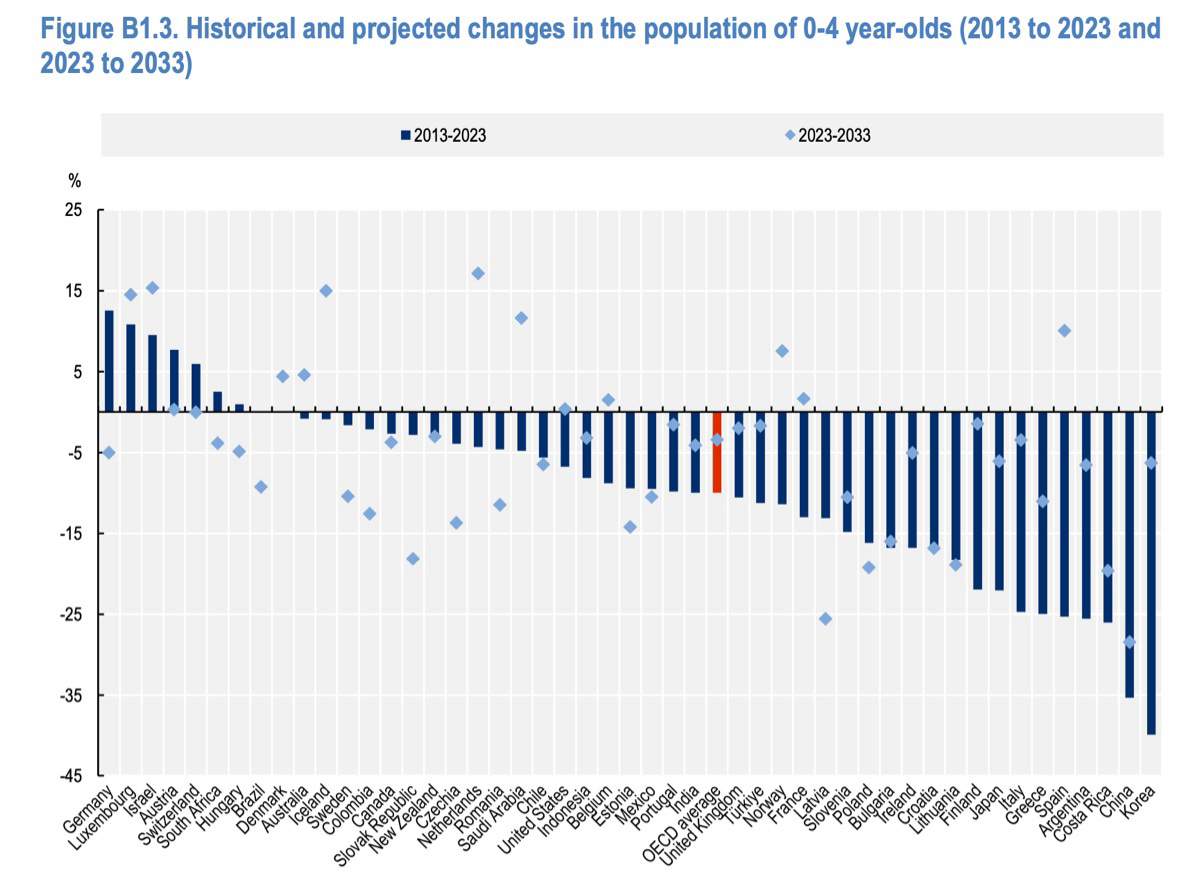

The OECD's Education at a Glance 2025, just released, confirms what this means for universities. The pipeline of young people is contracting rapidly. In some regions, the population of future university students will drop 15% over the next decade.

This isn't a distant problem. It's happening now.

What comes after massification in advanced economies?

The numbers are stark.

In several Eastern European countries, the 0–4 population is projected to shrink by more than 15% between 2023 and 2033, signalling a smaller tertiary‑age cohort in the 2030s.

When these smaller cohorts reach university age, there simply won't be enough students to fill existing capacity.

Meanwhile, graduation rates remain stubbornly low. Only 43% of students finish their degrees on time. Just 70% graduate within three extra years.

The math is unforgiving: fewer students entering, more dropping out.

This marks the end of massification in many advanced economies—the 60-year expansion from elite to mass higher education. These systems now face demographic contraction and institutional consolidation, with no guarantee that rising participation rates can offset shrinking youth cohorts.

Meanwhile, in regions such as Africa and South Asia, massification continues, underscoring how the global landscape of higher education is shifting before our eyes.

Why massification has hit a wall in advanced economies

Demographics aren't the only constraint.

In advanced economies, universities now face growth ceilings:

Costs outpace revenues due to Baumol's cost disease. You can't automate teaching the way you can manufacturing.

Aging populations drain government budgets toward healthcare and pensions, away from education.

Housing shortages create physical caps on enrollment, especially where international students concentrate.

Environmental and political pressures limit campus expansion.

Contrast this with growth trajectories in other regions:

In Africa, the number of young people completing secondary or tertiary education is projected to more than double by 2040; in South Asia, India aims to raise its gross enrolment ratio in higher education to 50% by 2035. In the Gulf States, governments are rapidly scaling new capacity to absorb domestic and international demand.

Market concentration of a few source countries and institutional distribution creates fragility in new geopolitics

Despite years of diversification talk, the global student market has a structural flaw.

It looks more like an hourglass than a globe: wide base of sending countries, narrow middle, choke-point of destinations.

The concentration is extreme:

58% of mobile students studying in OECD countries are from Asia.

The “big four” English-speaking countries (Australia, Canada, UK, US) host ~46% of internationally mobile students in OECD and partner countries, while the ”big ten” destinations are gaining momentum

The fragility of concentration varies by system:

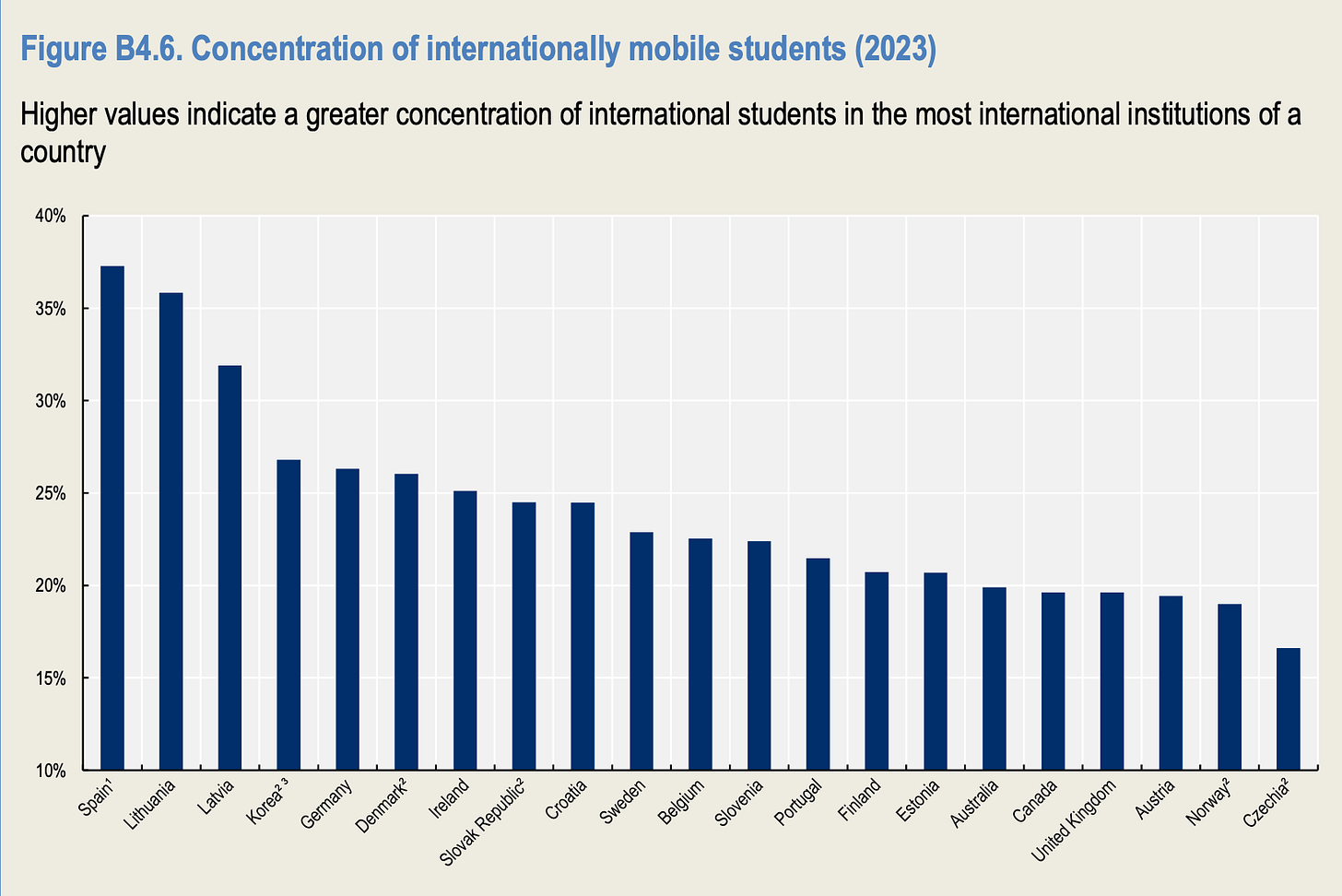

Spain has the highest concentration risk, with international enrollments clustered in relatively few universities. Although not included in the OECD report, Open Doors data show that the United States faces similar risks, with more than 55% of international students concentrated in research-intensive universities, which make up only about 5% of the 4,000 degree-granting institutions.

In Australia and the United Kingdom, international students are relatively more spread across many universities, producing high system-wide exposure, but with distributed risk. International students in Canada are present even in smaller colleges, reducing the chance of collapse at any single institution (though housing capacity has become a growing national challenge), and Austria, like Canada, shows a broad distribution of international students across institutions.

Czechia represents the most even distribution of international students across its relatively small system.

Welcome to the Age of Conquest

U.S. mega-universities: Concentrate at the top

This concentration dynamic isn't unique to international flows or American institutions.

’s analysis of US higher education reveals what he calls an "Age of Conquest"—even as overall enrollment peaked in the early 2010s and has declined since, the largest 120 institutions have grown their market share from 22% to 27%. The biggest get bigger while smaller colleges close.Advanced economies: Consolidate to compete

I’ve been noticing a similar pattern worldwide:

In the UK, over 40% of universities are now forecasting deficits, amid weaker international recruitment following visa policy tightening—fueling course closures and even talk of “super-universities.” Japan’s sshrinking youth population is driving government-backed mergers and closures in the private sector, while South Korea’s Parliament has passed a law enabling authorities to shut failing private universities.

Australia is betting on scale by creating Adelaide University in 2026, self-described as “South Australia University for the Future”, through the merger of two major institutions.

Across these cases, the pressures differ—demographic collapse, fiscal strain, or global competition—but all point to the same outcome: consolidation at the top, closures at the margins.

Global EdTech: Expansionist ambitions

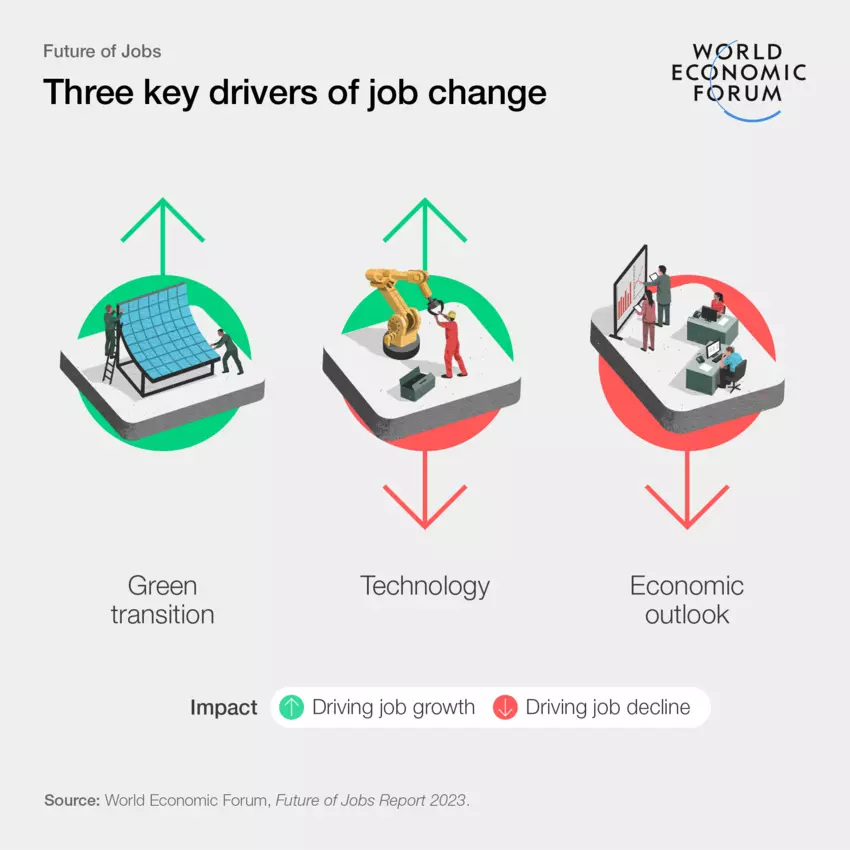

And let’s not forget the fast-growing technology sector emerging outside traditional university governance that

spotlighted in her incisive analysis, “Degrees of Separation”–a “digital system” that runs in parallel to the “traditional system” of international education.Ambitious and highly capable technology companies are not just experimenting at the margins—they’re moving aggressively to fill the gap left by universities that have been slow to respond to dramatic labor-market shifts.

They’re constructing a parallel learning architecture at industrial scale—think Google Career Certificates with over a million graduates; IBM SkillsBuild, which aims to reach 30 million learners; or Campus.edu, which has raised more than $100 million (with backing from Sam Altman) to position itself as a transfer-friendly, career-oriented alternative to community and technical colleges. Their scale, speed, and data-driven reach far outstrip what most universities can imagine, operating alongside—and increasingly in competition with—traditional higher education.

The shift from global flows to regional spheres

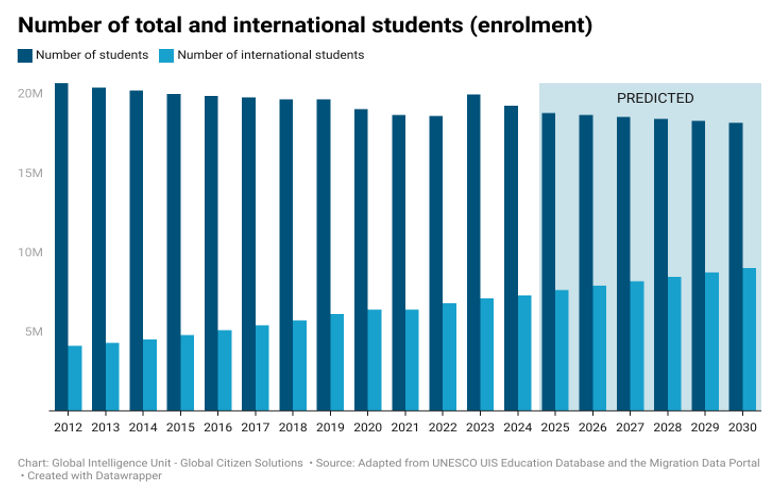

Meanwhile, student mobility isn’t slowing; it’s just dispersing across regional spheres—on track for roughly 10 million students studying abroad by 2030.

International students are not just “filling seats” but “filling gaps” left by shrinking cohorts in advanced economies, where demographic decline now collides with structural post-growth pressures.

Geopolitical theorist Parag Khanna describes our era as one of “high entropy”—energy dissipating rapidly and chaotically through the global system. His Periodic Table of States frames this not as a breakdown but as a reordering, where stability—the composite of strength and stateness—becomes the real currency of power.

What he describes as the “regression from the Westphalian world to the neo-medieval” captures what’s happening to student mobility: the collapse of unipolar flows into layered sovereignties with competing authorities and shifting alliances.

This marks the end of Anglo-American dominance as students flow along regional logics rather than just toward the Big Four destinations. Countries practice "multi-alignment," where a more diverse set of countries exerts greater relative influence.

De-risking in an era of “responsibile internationalization”

As Hans de Wit and I argued in “Navigating the Political versus Social Realities of ‘Responsible Internationalization’”, openness is no longer automatic in an era of “responsible internationalization” where international partnerships are getting greater scrutiny from elected officials.

Security risks

Governments now calibrate student flows with surgical precision:

Belgium caps high-demand programs

Denmark restricts English-taught courses

The Netherlands debates language requirements and intake limits

Security ministries increasingly shape the landscape. Research security regimes filter by field—visa controls target AI, bioscience, and engineering.

Today's student mobility is shaped by strategic education blocs and regional security complexes as much as admissions committees.

This isn't a cyclical fluctuation; it reflects structural realignments where national security increasingly overrides market logic.

Economic risks

For many countries, universities’ financial dependency on international students is now a structural demographic necessity, not just a source of supplemental revenue.

Almost one-third of university funding comes from private sources and about two‑thirds of that private share comes from households (tuition and fees).

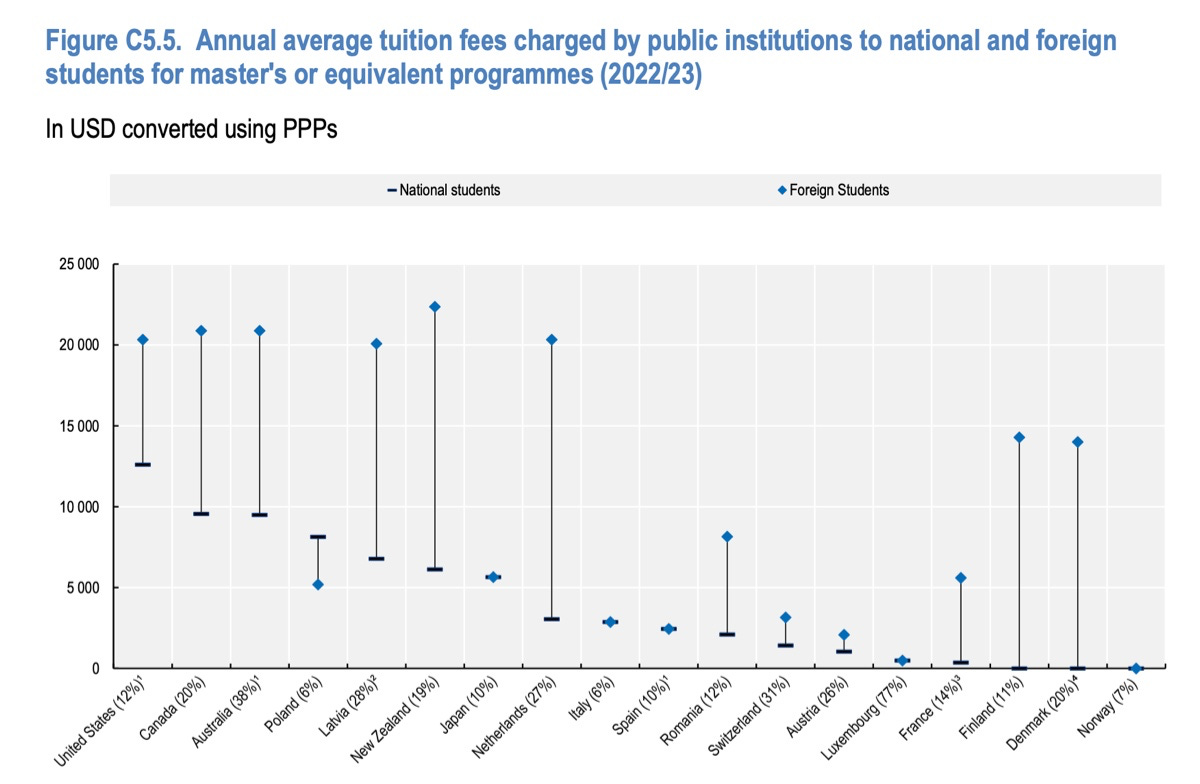

Two-thirds of countries charge international students premium rates—often exceeding $10,000 USD more per year than domestic students.

In the U.S., the structural dependence on attracting premium international students is already showing its limits. NAFSA projects a $7 billion revenue loss and 60,000 fewer jobs this academic year tied not to the US inability to attract students, but policy-induced frictions that reduce its absorption capability.

This has implications beyond the current budget cycle, as international students are just “supplemental income”; they are essential scientific infrastructure.

Attraction is no longer enough: Attraction ≠ Absorption

The old argument was simple: build world-class universities and the world’s talent will come. A frictionless “global marketplace,” a free trade of minds.

Today’s reality is different. National policies add friction to student flows much like tariffs restrict international trade.

The old logic was clear: build universities to attract students and announce record highs each year.

The new logic is harder: build systems to absorb students and measure how well they succeed.

Success now depends on managing four HALO absorption factors:

Housing: Physical capacity to accommodate students

Affordability: Total cost burden students can bear

Labor: Work authorization and career integration pathways

Openness: Visa policies and security screening processes

In the end, absorption is higher education’s version of strength plus stateness. The real measure of stability isn’t how many students arrive, but how well systems convert inflows into durable outcomes for students and tangible benefits for the societies that host them—benefits strong enough to generate broad popular support.

Today’s policy choices will redirect who moves, where, and why

The trend lines are clear: populations are already declining in some countries and stagnating in others, with fertility rates falling far faster than most projections anticipated.

In advanced economies, post-massification stagnation now collides with post-growth financial pressures. That collision does not spell collapse; it marks a redistribution: of where students go, why they move, and the importance of strategic policy choices.

The old logic was simple: demand would rise, enrollments would grow, and tracking inbound mobility was a sign of health.

The new logic is more complex: security, demographics, and absorption capacity—not just demand—will redirect who moves, where, and why.

For policymakers and leaders, this means moving beyond headline counts of international arrivals, whether it’s celebrating record highs or projecting record declines.

What matters now is for national policymakers to recognize this new reality and translate mobility—whether through brain gain, circulation, or linkage—into real capabilities and lasting benefits for students and for the nations where they study, live, and (perhaps someday) work.

What do you think?

How will these demographic declines reshape student flows? How will nations and institutions adapt? And what am I missing?

I’ll be at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) on November 6 at 7:00pm ET in the Wong Auditorium debating the motion:

“US universities are too dependent on international students.”

I’ve been invited by the MIT Free Speech Alliance to argue against the motion, and I’m grateful for the opportunity to engage in an open, civil exchange on such an important topic.

I’ve carefully considered the evidence on both sides and know I’ll have my work cut out for me. But whether I “win” or “lose,” the real victory is for democracy when people with different viewpoints can debate openly and respectfully.

If you live in Greater Boston, you’re welcome to attend, and we can connect. If not, I’ll share the video of the debate with this community once it’s posted. I’ll also share what I learn from the exchange of ideas and people who hold different perspectives.