I shared the following remarks at a recent AIEA Thematic Forum.

I'm grateful to be among people who share a commitment to international education.

Our field needs it. But our field also needs some serious reality testing. So, I hope you don't mind if I take the next 30 minutes to unsettle some popular misconceptions about belonging and share my honest assessment of the current state of affairs.

If we care about the field, we must confront hard truths as we approach the future of international education.

We must reconsider what belonging means in an era of geopolitical realignment–international education has moved from

‘We will give you a space’ (Cold War), to

‘You can buy a space’ (market liberalization), to

‘You must secure a space’ (Cold War 2.0).

I will explore this new era of internationalization more at the end.

The Adaptive Challenge Before Us

We are at a critical moment in higher education that demands adaptive leadership.

Let's be frank:

We've entered a fundamentally different era of internationalization.

Leadership will involve coaching our executive teams through adaptive challenges, not technical ones.

Technical challenges are things like cyclical enrollment fluctuations due to budget cuts. Technical challenges are easy to identify, have known solutions, and can be solved based on expertise or by authorities.

Adaptive challenges, the kind our field will face in the coming years, are difficult to identify—frankly, because they're easy for most people to deny. They lack straightforward answers and require new learning and experimentation. Adaptation requires a shift in our beliefs, habits, roles, relationships, and approaches to work.

We can't keep doing what we've always done.

This fundamental shift in orientation is precisely why we need to reconsider belonging as not just a comforting ideal, but as a complex, sometimes challenging reality.

We've entered a fundamentally different era of internationalization. Leadership will involve coaching our executive teams through adaptive challenges, not technical ones.

Belonging: The Gateway to Global Learning

Ten years ago, I wrote a piece called "Belonging: The Gateway to Global Learning for All Students."

In that piece, Larry Braskamp and I discussed our research from the Global Perspectives Inventory (GPI). 100,000’s of students have completed the GPI as part of study abroad experiences. But when Larry designed it, he wanted to look at all kinds of experiences students have in college—not just study abroad, but engagement with faculty, classroom conversations across difference, campus leadership roles, and multicultural opportunities.

We found a strong connection between the amazing experiences already happening on campus and the educational outcomes we aspire to in higher education. We found that students' commitment to global learning developed through meaningful faculty interactions, participation in service learning opportunities, classes that involved dialogue across different points of view, and leadership opportunities.

We found that belonging was a gateway to global learning for all students, whether they had traveled abroad or not.

Belonging was not merely about identity-based membership, but collective action and shared practices–a lesson as old as Gordon Allport's contact hypothesis.

What was true 10 years ago is true today:

There continue to be many gateways to global learning, but they all have the same element at their core: belonging. When students belong, they become more receptive to diverse perspectives, more willing to engage with unfamiliar ideas, and more capable of developing intercultural competencies.

But belonging is far more than the sentimental notion–it’s something harder and more resilient, and more essential than ever as we enter the next era of internationalization.

If you belong, you hardly think about it. If you don't, you think about it all the time.

Belonging as Experience

You might ask: “So, what's your definition of belonging?”

This might come as a shock: I don't have one.

We don't define belonging—we experience it.

Western tradition often seeks the "right definition," but belonging is somatic and embodied—it resists abstraction. We feel it viscerally, often from experiencing its opposite. Have you ever felt alienated? Excluded? Isolated? Rejected? Marginalized? These experiences are more painful than many forms of physical suffering.

If you belong, you hardly think about it. If you don't, you think about it all the time.

The Evolutionary Roots of Belonging

We know belonging not as a definition but as an experience. That's because it's an experience that is as deep as the evolution of our species.

In their influential 1995 Psychological Bulletin article "The Need to Belong," evolutionary psychologists Roy Baumeister and Mark Leary presented compelling evidence that belonging constitutes a fundamental human motivation.

Belonging is not a fad or trend, even though you will find 100’s of books about it on Amazon. Belonging is a fundamental truth—as true today as it was 30 years ago, 300 years ago, 3,000 years ago, 30,000 years ago, 3 million years ago.

Belonging is etched in our DNA—it forms the very architecture of our shared humanity. Our fundamental need to belong remains primal, woven into the deepest layers of our psyche.

In The Social Conquest of Earth, E.O. Wilson challenges traditional views on natural selection by advancing multilevel selection theory—revealing how our capacity for belonging and cooperation became central to humanity's evolutionary success.

Humans didn't rise to become Earth's dominant species through physical prowess—countless creatures surpass us in strength, speed, and natural defenses. Our ability to cooperate in complex social groups became our defining evolutionary advantage. Cooperative groups survived; fractious communities withered.

As Martin Luther King urged: "We must learn to live together as brothers or we will die together as fools."

Belonging is etched in our DNA—it forms the very architecture of our shared humanity. Our fundamental need to belong remains primal, woven into the deepest layers of our psyche.

Beyond the B in DEIB

Belonging appears self-evidently beneficial—an unassailable good.

As Terrell Strayhorn has argued, belonging in a collegiate context is the way a student perceives their connection to their university community. This perception influences academic performance, persistence, and overall well-being.

Students who feel they belong graduate at higher rates, and international students who belong experience greater academic success. Do we really need studies to prove this? The evidence for our innate need to belong is incontrovertible.

But the apparent consensus obscures a more complex reality.

As Arthur Chan observed, "Diversity is a fact; equity is a choice; inclusion is an action; and belonging is an outcome."

I agree with this elegant formulation. But I don't think it goes far enough. Belonging is more than an outcome. It is a gateway to something much bigger.

Reimagining Maslow's Hierarchy

In popular psychology, belonging occupies the middle of Maslow's famous pyramid—right above safety needs and just before esteem.

Yet few realize Maslow never conceived of his framework as the rigid pyramid we see in our Psychology 101 textbooks. This widespread misconception reduces belonging to something fragile, like the middle block of a Jenga tower that, if removed, causes everything to collapse. Such thinking wrongly suggests that humans are inherently fragile—that even the slightest experience of rejection risks everything falling apart.

As Scott Barry Kaufman convincingly argues, Maslow never created a pyramid. Life isn't a trek up a summit. It's more like a vast ocean, full of opportunities for meaning and discovery, but also danger and uncertainty. In this choppy surf, a pyramid is of little use. What we need is something more flexible: a sailboat.

Belonging is part of the boat's hull, alongside safety and self-esteem. These elements collectively provide the stability necessary to stay afloat and weather life's challenges. Kaufman's reimagining of Maslow shifts the focus from achieving a fixed state to navigating life's complexities with resilience and adaptability.

Why is belonging essential?

Not merely as an outcome but as a hull that allows all students to weather life's storms on individual and collective journeys towards transcendence.

It serves as the keel for building resilient students, communities, and universities–it serves as a catalyst that enables people to discover purpose, experience love, and engage in the exploration that makes life meaningful.

So, what does it mean when we claim that belonging serves as a gateway to global learning for all students?

We want every student who comes to our universities to discover their full potential, to explore possibilities they've never imagined, and to evolve beyond their initial self-concept. What we're really seeking is self-transcendence—what is "higher" about higher education?

We also want our society to undergo its own transformation, to resist systems of oppression or exclusion, and to change itself as well.

So, belonging is not just an outcome; it's a gateway to something much greater than ourselves. Belonging is the gateway to global learning for all students because global learning is about becoming part of something much bigger than ourselves.

The Messy Complexity of Belonging

Belonging is not just any experience. It’s a complex, messy experience.

In his comprehensive analysis of scholarship on belonging, Marco Antonsich found that despite its widespread use in academic literature, the concept of "belonging" is rarely defined explicitly. His research reveals two distinct dimensions of belonging that are frequently conflated:

Place and Politics

In one sense, belonging is about "place". When we speak of belonging, we often think of it as attachment to a place, community, university, or group. It's that personal, intimate feeling of being at home—a sense of ease with oneself and one's surroundings, operating beneath our conscious awareness.

But belonging is also about "politics". It involves "the dirty work of boundary maintenance". It involves the power to define who belongs and who doesn't through policies, practices, and discourses. Who belongs here? When someone asks an international student, "Where are you from?" the subtext is sometimes, "Why are you here?" That boundary work of who belongs, who's included, who's excluded.

Belonging as both "place" and "politics" is important to recognize because they are inseparable.

A student may feel personally at home on campus (place-belongingness) yet encounter visa restrictions or nationality-based surveillance that challenge their right to be there (politics of belonging). Conversely, a student may have legal permission to study (formal inclusion) yet feel alienated in daily campus life (absence of place-belongingness). Consider students from China and Hong Kong "living in fear of intimidation, harassment and surveillance" with many afraid to return home.

Understanding both “place” and “politics” helps us move beyond simplistic models that reduce belonging to individual feelings without considering power structures.

Belonging is Multidimensional

Belonging is not just messy, it’s multidimensional.

Let's further unpack place + politics across a spectrum.

Relational: Interpersonal Bonds and Social Networks

Relational belonging encompasses connections with faculty, peers, co-nationals, and international students, spanning the spectrum from deep friendships to everyday interactions, while also including transnational bonds sustained through digital technologies.

The core of Baumeister and Leary’s (1995) definition emphasizes "a pervasive drive to form and maintain lasting, positive, and significant interpersonal relationships" through "frequent, nonaversive interactions within an ongoing relational bond." For these interactions to satisfy the need to belong, they must be characterized by two essential features: (1) regular positive interactions and (2) a perception of an ongoing, stable relationship marked by mutual concern.

Cultural: Engagement and Meaningful Contribution

Cultural belonging is not just about representation— it’s about relevance and responsiveness. Language forms the foundation, but it extends to shared values and active participation in shaping our institutional cultures. It's not simply about learning American football traditions, but recognizing that your university becomes fundamentally different because you were there.

True belonging isn't achieved merely by fitting into existing structures, but through "the right to participate in the development of the 'living tradition.'" Belonging isn't a program, welcome week, or orientation. It's about empowering students' agency to engage in placemaking on our campuses.

Spatial: Navigating Campus Spaces and Places

Physical environments—address the material environments where belonging is experienced or challenged. From dormitories and classrooms to neighborhoods and local communities—campus environments are not static buildings but dynamic settings that invite (or inhibit) students to transform “spaces” into “places” they have built and shaped for new generations of students to inhabit and build upon.

I’ve done research with a colleague, Ed Gomez, who created the Ethnicity and Public Recreation Participation Model that explores the role of race and ethnicity in recreational and park spaces. Parks appear neutral—”Everybody can play in the park, right?”—but that's not how everyone experiences these "open" spaces.

Our campus spaces, walkways, and pathways aren't neutral either. When Cheryl and I worked on her campus, instead of asking, "How do we get international and domestic students to interact?" we asked, "Where are they already interacting? How can we learn from the spaces and extend that to other spaces on campus?"

Economic: Financial Security and Employability

Economic belonging encompasses both immediate financial stability and long-term employability. Financial security and integration into economic systems profoundly impact belonging. Students with scholarships or campus employment may experience greater stability than those struggling with financial precarity. Pathways to employment beyond graduation matter.

I recently posted about international student numbers declining in the SEVIS database, and someone privately messaged me: "Hey, I noticed students from India are revoking their SEVIS records earlier. They're going home because they can't find jobs." Their parents are saying, "Let's go home. Why don't you just come back home where you belong?" That comment received a huge number of reactions, with many people seeing the same pattern.

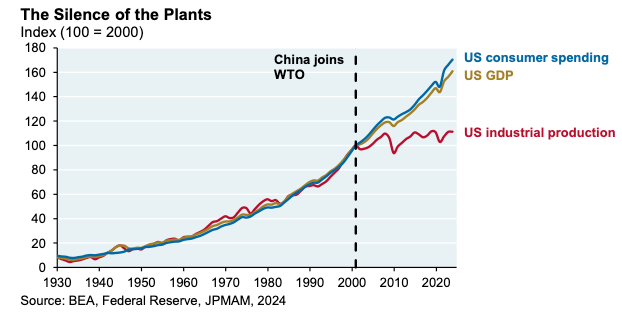

This leads to a harder truth our field must address more directly. When China joined the World Trade Organization (WTO) in 2000, it created a fundamental economic divide. Regions that once thrived with manufacturing saw their industrial base collapse—factories shuttered, communities hollowed out, livelihoods vanished.

Economists have documented this phenomenon precisely: despite overall GDP growth and rising consumer spending nationally, American industrial production stagnated or declined in many regions—a phenomenon they've termed "the silence of the plants."

So, when some students say, "This global stuff isn't for me," it's because belonging is visceral. They've experienced globalization in ways many of us haven't. I've benefited from the last 20 years of globalization—but many people haven't, and they've felt it. They've felt alienated, excluded, isolated, rejected, marginalized. And, until we acknowledge that—like in any broken relationship—it's hard to move forward. We need truth before reconciliation. We need to recognize how economic inclusion and exclusion have affected belonging for many of the students we serve.

Belonging is not a feeling; it's an economic reality. US higher education is increasingly unaffordable for domestic and international students. NAFSA's Benchmark Enrollment Report highlighted many international students simply can’t afford an education in the US. As costs have risen, trust in higher education has plummeted.

Legal: Frameworks for Status and Participation

The legal dimension of belonging matters too. Visa status, work permissions, and pathways to residency create the essential legal framework within which international students exist. With over 1,800 visa revocations across all types of higher education institutions, uncertainty has infused the experience of a growing number of international students.

Billy Wong calls attention to the structural dimensions of belonging, which focus on how societal systems and dominant policies shape the way space and relationships are experienced by international students. His approach recognizes how legal frameworks and policies are "imbued within complex power relations" that reflect the politics of belonging that international students experience.

This multidimensional perspective avoids reducing “belonging” to just one dimension. It illuminates belonging as a complex — and often contradictory – sets of experiences. A student might have strong relational connections, but also experience economic insecurity or legal status uncertainties simultaneously.

The Freedom of “Not Belonging”

You might think I'm arguing everybody should belong–akin to Disney's saccharine High School Musical, "We're all in this together."

If I polled you on whether everybody should belong, we'd probably all agree.

The outsider gains the capacity to see both the visible and invisible structures that organize social life. When systems or institutions are harmful or unjust, 'not belonging' becomes an act of integrity.

The Outsider's Perspective

The conventional view frames "not belonging" as inherently negative—a deficit state characterized by exclusion, alienation, and psychological distress. This binary thinking, however, fails to capture the complex reality and transformative potential contained within the experience of “not belonging”.

Far from being merely the absence of belonging, “not belonging” can possess its own generative qualities.

Let's do a philosophical experiment: consider the freedom of not belonging.

I know this from my own life. I've experienced trauma, alienation, and exclusion in ways I've never discussed publicly. I know what it feels like not to belong, and I imagine many of you do too—stories you may not share.

But there's something profoundly liberating about that experience, because you actually see the system. You see who it's rigged against and who it supports. That freedom can lead to breakthroughs that are quite empowering.

The outsider gains the capacity to see both the visible and invisible structures that organize social life. When systems or institutions are harmful or unjust, “not belonging” becomes an act of integrity.

“Belonging” vs “Fitting In”

Do we always want to belong?

As Brené Brown points out: “The opposite of belonging is fitting in... True belonging never asks us to change who we are, it demands we be who we are.”

Often when we say, "We want you to belong at our university," we're really saying, "We want you to fit in here."

But sometimes it's okay, good, and healthy not to belong because the systems we're invited to "belong to" (really fit into) aren't systems we want to perpetuate.

"Not belonging" becomes paradoxically the precondition for a more profound form of freedom—one that transcends the limitations imposed by fixed identity categories and group affiliations.

Belonging Nowhere and Everywhere

Maya Angelou offers this profound perspective:

Her view was that in some ways, she belonged everywhere and nowhere—a tension that gave her freedom to speak hard truths.

If you think about scientific breakthroughs, artistic movements, and social transformations that have changed the world, they emerged from individuals and communities positioned at the margins rather than the center.

This creative tension between belonging and not-belonging becomes especially significant as we navigate what I believe is a fundamentally new era in international education—one where traditional approaches to belonging are being disrupted by geopolitical forces that demand new frameworks and leadership strategies.

A New Era in International Higher Education

As I mentioned at the start, I believe we are in a new era of internationalization, as different as the shift from the end of the Cold War to the most recent era of market liberalization.

While time will be the ultimate judge of whether I am correct, my assessment comes from deep reflection and rigorous analysis of current global trends. It isn't mere speculation or a reaction to yesterday's news. The evidence is substantial.

Each historical era shapes its own distinct conception of belonging.

I invite you to consider whether we have entered a new Cold War.

Unlike the original Cold War characterized by ideological standoffs and military alliances between superpowers, the new Cold War revolves around technology supremacy and economic competition that will fundamentally restructure the post-World War II liberal democratic order—with its Bretton Woods institutions, multilateral cooperation, and rules-based international system.

Tariffs and trade wars mark the opening salvo of an intensifying strategic confrontation between the US and China—one that threatens to bifurcate the global order and splinter alliances among Middle Powers caught between these competing superpowers.

Cold War Era (1945-1990): "We Will Give You a Space"

During the first Cold War, international student mobility served as a tool of ideological competition. The 1946 Fulbright Act institutionalized academic mobility as statecraft, creating a pipeline that brought 30,000 foreign students to U.S. universities by 1950—a 328% increase from 1945.

In this era, belonging was structured through ideological alignment. Students were "given" a place, often by the state, under cultural diplomacy frameworks. Programs like Fulbright legitimized belonging through ideological utility, with students received as representatives of allied nations.

The politics of belonging dominated in this era, with place-belongingness subordinated to geopolitical objectives. Students' personal experiences mattered primarily as evidence of successful soft power. "Spaces" were provided, but students had limited agency in transforming them into "places" of personal belonging.

In the Cold War era, the dominant rationale was political, with international student mobility serving as a tool of ideological competition and cultural diplomacy.

This form of belonging was hierarchical, conditional, and often temporary. Hospitality was statecraft, not solidarity, and the right to belong was contingent on advancing Cold War objectives. As this ideological competition gave way to market liberalization, the very nature of belonging in international education transformed from state-sponsored integration to consumer-based participation.

Market Liberalization Era (1991-2016): "You Can Buy a Space"

The collapse of the Soviet Union gave rise to a new rationale: neoliberal logic reframed students as consumers and universities as global brands in an education marketplace.

The General Agreement on Trade in Services (GATS) framework transformed higher education into an export commodity. By 2020, international student tuition generated over $40 billion for U.S. institutions. Meanwhile, foreign government support fell, with two of three international students relying on personal funds.

During market liberalization, "everybody could have a space"—if they could pay for it. Students around the world were willing to pay for US higher education, as the rising middle class in China, India, and other countries gained economic power.

In the Market Liberalization era, the dominant rationale became economic, as neoliberal logic transformed higher education into an export commodity and international students into “cash cows”, consumers who purchased access to education if they had sufficient financial resources, generating billions.

Belonging was depoliticized as market logic prevailed. Capital, not citizenship, determined access. It became transactional.

This market model proved brittle, however—and vulnerable to geopolitical conflict.

Cold War 2.0 (2017-Present): "You Can Secure a Space"

We are now witnessing the most profound restructuring of global student mobility since the end of the Cold War. The frictionless market-based model is unraveling before our eyes as techno-nationalism reshapes government policies.

This new Cold War centers on technological competition: semiconductors, quantum computing, 6G networks, rare earth materials, AI capabilities, and information control. The university has become a contested site in this competition. International students must negotiate complex power structures that determine who belongs.

The intensifying U.S.-China rivalry is deepening global divisions, with the effects reverberating across economies and societies worldwide. Global visa denial rates have climbed sharply—from 15% in 2000, to 25% in 2015, and reaching 41% in the most recent year of the Biden administration

In the Cold War 2.0 era, the dominant rationale has shifted to security and technological competition, as cultural and social rationales fade and tensions between economic benefit and national security are heightened.

In this new era, belonging has become more precarious and contingent. The politics of belonging has reasserted itself through security discourses that question international students' right to be present. At the same time, economic imperatives create contradictory pressures for both openness and restriction.

You can see this new era of technological securitization in how the US government uses available information regarding the politics of belonging. Marco Rubio's "Catch and Revoke" policies rely on AI-assisted reviews of tens of thousands of student visa holders' social media accounts. The federal government collected information about undocumented immigrants through financial aid systems, and is using that data to identify students now receiving self-deportation emails.

The Path Forward

What do we need to do?

This era demands not just new analysis, but new approaches to leadership.

As leaders working with our teams in international education, we must help them recognize this shift not as a temporary swing of the pendulum but as a fundamental realignment requiring adaptive leadership. Enrollment declines won't be solved by better marketing; they're a signal of deeper geopolitical shifts requiring fundamental institutional adaptation.

Adaptive Leadership for Adaptive Challenges

This moment is a time for radical self-inquiry.

We need to lead.

I'm not hopeless. We have power. As Foucault reminds us, power isn't something that some possess and others lack—it flows through all of us. We actively exercise power through our choices and actions. And in this critical moment, we can deliberately channel the power we have to create change.

But that requires honest conversations about reality, not denial, so our teams can confront adaptive challenges that require changing our values, beliefs, and approaches to our work.

In this moment, the Serenity Prayer comes to mind:

"God, grant me the serenity to accept the things I cannot change, the courage to change the things I can, and the wisdom to know the difference. "

Jerry Colonna, in his book, Reunion: Leadership and the Longing to Belong, invites leaders to ask:

"How have I been complicit in creating the conditions I don't want?" and "What do I need to give up, even if I love it, to create systems of belonging that I do want?"

At this moment, we need not just serenity but clarity. A prayer like:

"Grant us the courage to see the world clearly, the ability to face our own complicity, and the will to change to create the world we want."

What's happening isn't just a technical correction. It's an adaptive challenge.

In Cold War 2.0, belonging isn't sentimental—it's strategic. The way forward will reflect how societies imagine our collective futures, who we include or exclude, and how we build resilience across difference.

Belonging as a Strategic Imperative

In Cold War 2.0, belonging isn't sentimental—it's strategic.

Some may romanticize past eras of cultural exchange. Others may long for the predictability and returns of market liberalization. But the times they are a-changin'. What was once a gift, then a transaction, is now about securing a position.

We need honest conversations about what it means to include students who felt excluded from the last 20 years of globalization—what it means for belonging to be a gateway to global learning for all students.

These conversations must be grounded in the multidimensional understanding of belonging we've explored—recognizing its relational, cultural, spatial, economic, and legal aspects, while acknowledging both the place-attachments and power politics that shape who belongs in our institutions.

UNESCO Reimagining Our Futures Together offers three essential questions:

What should we continue doing?

What should we abandon?

What needs to be creatively invented afresh?

As we enter Cold War 2.0, belonging grows more complex, more contradictory.

The “end of belonging” isn't about its disappearance. It’s the abandonment of our sentimentalized notions of it. Belonging has become both essential and precarious. It demands moral clarity and moral imagination.

We ask the wrong question when we wonder if students belong to our institutions. The real question: Can our institutions belong to them?

What are your thoughts?

What am I missing? Which dimensions of belonging in international education deserve more attention than my analysis provides?

What do you see? Are you observing patterns in your institution that confirm or challenge the Cold War 2.0 framework I've proposed?

What's next? If this analysis is correct, what specific changes to international student recruitment, support, or engagement do you predict will become necessary within the next 5 years?

I really resonated with this article! Arturo Escobar's ideas in his work Pluriversal Politics come to my mind, in which he reimagines the world as consisting of many different 'realities', with no reality being inherently more 'real' than another. With this understanding, we don't have to seek to 'fit in'. We can cherish differing realities (e.g., from the subaltern, indigenous knowledge, from marginalized groups outside the university's ivory tower...), take them seriously and learn from them, thereby collectively creating new, better futures without the need to adhere to only one version of what we understand as belonging.

Escobar uses some nice empirical examples to show how webs of local initiatives challenging dominant ontologies can lead to positive changes 'from the bottom up', such as indigenous groups fighting for the legal rights of nonhuman entities (example: a river gaining legal personhood in Colombia), thereby aiding environmental justice. As you write, breakthroughs often emerge from the margins.

I wonder whether new forms of free collaborative knowledge creation outside of universities, akin to the anthropologist Tomas Sanchez Criado's "experimental collaboration", could be integrated into accepted academic discourses across disciplines as well as learning practices in higher education. How could localized knowledge outside institutions'/governments' constraints be integrated in more macro discourses? Which technologies could help here perhaps? Which would need to be developed to serve this purpose?